Running Aspen via Python

Posted June 14, 2013 at 10:23 AM | categories: programming | tags: aspen

Aspen is a process modeling tool that simulates industrial processes. It has a GUI for setting up the flowsheet, defining all the stream inputs and outputs, and for running the simulation. For single calculations it is pretty convenient. For many calculations, all the pointing and clicking to change properties can be tedious, and difficult to reproduce. Here we show how to use Python to automate Aspen using the COM interface.

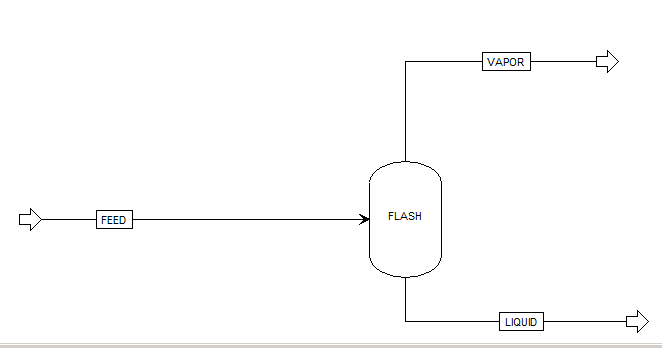

We have an Aspen flowsheet setup for a flash operation. The feed consists of 91.095 mol% water and 8.905 mol% ethanol at 100 degF and 50 psia. 48.7488 lbmol/hr of the mixture is fed to the flash tank which is at 150 degF and 20 psia. We want to know the composition of the VAPOR and LIQUID streams. The simulation has been run once.

This is an example that just illustrates it is possible to access data from a simulation that has been run. You have to know quite a bit about the Aspen flowsheet before writing this code. Particularly, you need to open the Variable Explorer to find the "path" to the variables that you want, and to know what the units are of those variables are.

import os import win32com.client as win32 aspen = win32.Dispatch('Apwn.Document') aspen.InitFromArchive2(os.path.abspath('data\Flash_Example.bkp')) ## Input variables feed_temp = aspen.Tree.FindNode('\Data\Streams\FEED\Input\TEMP\MIXED').Value print 'Feed temperature was {0} degF'.format(feed_temp) ftemp = aspen.Tree.FindNode('\Data\Blocks\FLASH\Input\TEMP').Value print 'Flash temperature = {0}'.format(ftemp) ## Output variables eL_out = aspen.Tree.FindNode("\Data\Streams\LIQUID\Output\MOLEFLOW\MIXED\ETHANOL").Value wL_out = aspen.Tree.FindNode("\Data\Streams\LIQUID\Output\MOLEFLOW\MIXED\WATER").Value eV_out = aspen.Tree.FindNode("\Data\Streams\VAPOR\Output\MOLEFLOW\MIXED\ETHANOL").Value wV_out = aspen.Tree.FindNode("\Data\Streams\VAPOR\Output\MOLEFLOW\MIXED\WATER").Value tot = aspen.Tree.FindNode("\Data\Streams\FEED\Input\TOTFLOW\MIXED").Value print 'Ethanol vapor mol flow: {0} lbmol/hr'.format(eV_out) print 'Ethanol liquid mol flow: {0} lbmol/hr'.format(eL_out) print 'Water vapor mol flow: {0} lbmol/hr'.format(wV_out) print 'Water liquid mol flow: {0} lbmol/hr'.format(wL_out) print 'Total = {0}. Total in = {1}'.format(eV_out + eL_out + wV_out + wL_out, tot) aspen.Close()

Feed temperature was 100.0 degF Flash temperature = 150.0 Ethanol vapor mol flow: 3.89668323 lbmol/hr Ethanol liquid mol flow: 0.444397241 lbmol/hr Water vapor mol flow: 0.774592763 lbmol/hr Water liquid mol flow: 43.6331268 lbmol/hr Total = 48.748800034. Total in = 48.7488

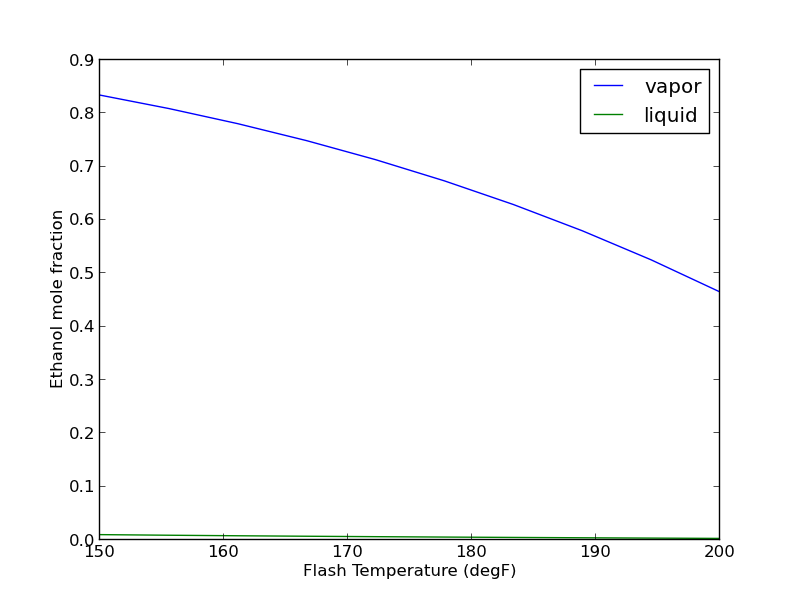

It is nice that we can read data from a simulation, but it would be helpful if we could change variable values and to rerun the simulations. That is possible. We simply set the value of the variable, and tell Aspen to rerun. Here, we will change the temperature of the Flash tank and plot the composition of the outlet streams as a function of that temperature.

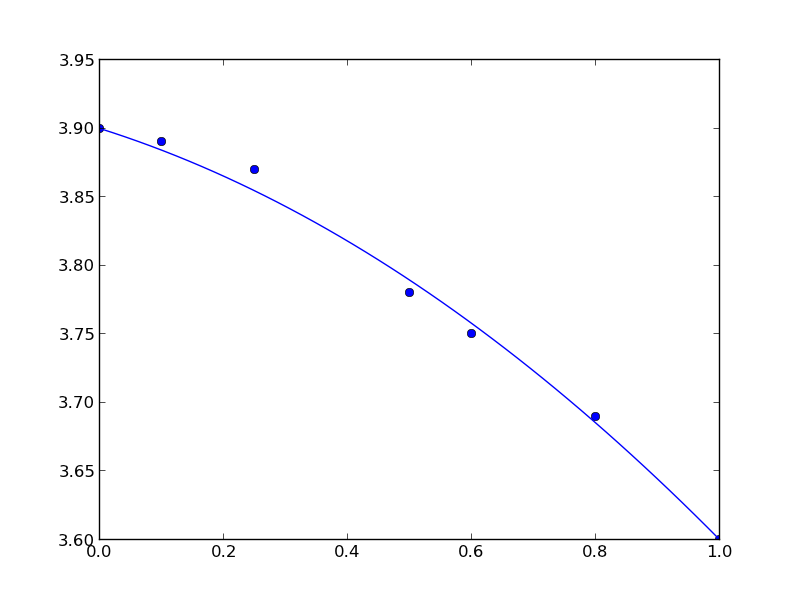

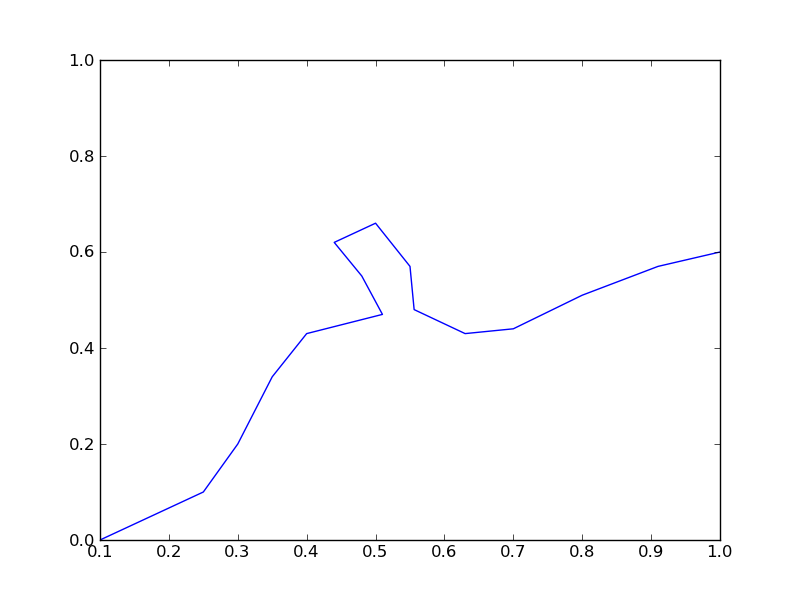

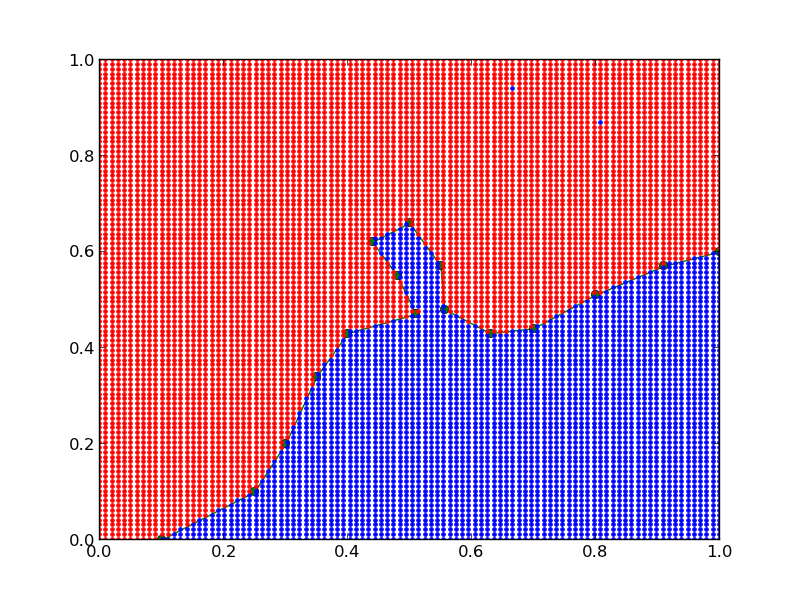

import os import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import win32com.client as win32 aspen = win32.Dispatch('Apwn.Document') aspen.InitFromArchive2(os.path.abspath('data\Flash_Example.bkp')) T = np.linspace(150, 200, 10) x_ethanol, y_ethanol = [], [] for temperature in T: aspen.Tree.FindNode('\Data\Blocks\FLASH\Input\TEMP').Value = temperature aspen.Engine.Run2() x_ethanol.append(aspen.Tree.FindNode('\Data\Streams\LIQUID\Output\MOLEFRAC\MIXED\ETHANOL').Value) y_ethanol.append(aspen.Tree.FindNode('\Data\Streams\VAPOR\Output\MOLEFRAC\MIXED\ETHANOL').Value) plt.plot(T, y_ethanol, T, x_ethanol) plt.legend(['vapor', 'liquid']) plt.xlabel('Flash Temperature (degF)') plt.ylabel('Ethanol mole fraction') plt.savefig('images/aspen-water-ethanol-flash.png') aspen.Close()

It takes about 30 seconds to run the previous example. Unfortunately, the way it is written, if you want to change anything, you have to run all of the calculations over again. How to avoid that is moderately tricky, and will be the subject of another example.

In summary, it seems possible to do a lot with Aspen automation via python. This can also be done with Matlab, Excel, and other programming languages where COM automation is possible. The COM interface is not especially well documented, and you have to do a lot of digging to figure out some things. It is not clear how committed Aspen is to maintaining or improving the COM interface (http://www.chejunkie.com/aspen-plus/aspen-plus-activex-automation-server/). Hopefully they can keep it alive for power users who do not want to program in Excel!

Copyright (C) 2013 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.