New publication - Semi-grand Canonical Monte Carlo Simulation of the Acrolein induced Surface Segregation and Aggregation of AgPd with Machine Learning Surrogate Models

Posted March 07, 2021 at 04:00 PM | categories: news | tags:

Updated June 24, 2021 at 04:37 PM

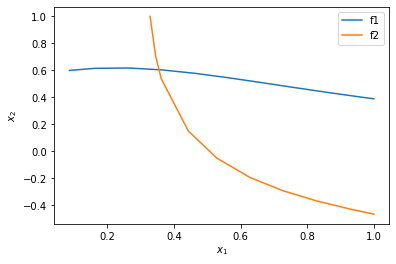

Modeling alloys is tricky, and modeling dilute alloys has been an open challenge for a long time. Segregation is one of the biggest challenges; the surface composition is not the same as the bulk, and is influenced by adsorption. Although we know that the composition varies to lower the surface free energy, the configurational degrees of freedom make it difficult to find the lowest energy arrangement of atoms. In the dilute limit, the quantum chemical calculations and Monte Carlo simulates we do become very expensive due to the unit cell size. In this work, we use machine learning to build surrogate models for the configurational energy of an alloy slab in the dilute limit. Then, we use those models in conjunction with a semi-grand canonical Monte Carlo (MC) simulation to solve several of these problems. First, by fixing the alloy chemical potential at the desired dilute limit, we avoid the need for large unit cells. Second, the surrogate models are much more efficient than DFT, so we can use them in the MC simulations to run tens of thousands of simulation steps to get the required samples for reliable statistical averaging. In dilute alloys, the focus is on the unique catalytic properties of single atoms of an active metal like Pd in an inert metal like Ag. In the single atom limit though, there are few active sites. If you increase the bulk concentration, at some point the single atoms begin to aggregate into dimers and trimers, and adsorbates can make the aggregation happen faster. Aggregation is undesirable because it usually leads to lower selectivity, and more bulk like reactivity. An open question has been how do you design alloy catalysts under reaction conditions, given all this complexity. We apply this approach to the adsorption of acrolein on a dilute AgPd alloy, and show how to use the method to identify the bulk concentration where aggregation begins in a reactive environment.

@article{liu-2021-semi-grand, author = {Mingjie Liu and Yilin Yang and John R. Kitchin}, title = {Semi-Grand Canonical Monte Carlo Simulation of the Acrolein Induced Surface Segregation and Aggregation of {AgPd} With Machine Learning Surrogate Models}, journal = {The Journal of Chemical Physics}, volume = 154, number = 13, pages = 134701, year = 2021, doi = {10.1063/5.0046440}, url = {https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0046440}, }

Copyright (C) 2021 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.

Org-mode version = 9.4.6