Autograd and the derivative of an integral function

Posted October 10, 2018 at 06:24 PM | categories: python, autograd | tags:

Updated October 10, 2018 at 06:32 PM

Table of Contents

There are many functions that are defined by integrals. The error function, for example is defined by \(erf(x) = \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}\int_0^x e^{-t^2}dt\).

Another example is:

\(\phi(\alpha) = \int_0^1 \frac{\alpha}{x^2 + \alpha^2} dx\).

We have reasonable ways to evaluate these functions numerically, e.g. scipy.integrate.quad, or numpy.trapz, but what about the derivatives of these functions? The analytical way to do this is to use the Leibniz rule, which involves integrating a derivative and evaluating it at the limits. For some functions, this may also lead to new integrals you have to numerically evaluate. Today, we consider the role that automatic differentiation can play in this.

The idea is simple, we define a function in Python as usual, and in the function body calculate the integral in a program. Then we use autograd to get the derivative of the function.

In this case, we have an analytical derivative to compare the answers to:

\(\frac{d\phi}{d\alpha} = -\frac{1}{1 + \alpha^2}\).

1 Example 1

For simplicity, I am going to approximate the integral with the trapezoid method in vectorized form. Here is our program to define \(\phi(\alpha)\). I found we need a pretty dense grid on the x value so that we have a pretty accurate integral, especially near \(x=0\) where there is a singularity as α goes to zero. That doesn't worry me too much, there are better integral approximations to use, including Simpson's method, adaptive methods and perhaps quadrature. If you define them so autograd can use them, they should all work. I chose the trapezoidal method because it is simple to implement here. Note, however, the autograd.numpy wrappers don't have a definition for numpy.trapz to use it directly. You could add one, or just do this.

import autograd.numpy as np from autograd import grad def trapz(y, x): d = np.diff(x) return np.sum((y[0:-1] + y[1:]) * d / 2) def phi(alpha): x = np.linspace(0, 1, 1000) y = alpha / (x**2 + alpha**2) return trapz(y, x) # This is the derivative here! adphi = grad(phi, 0)

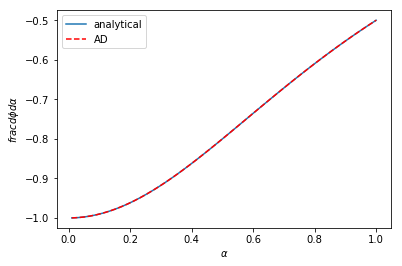

Now, we can plot the derivatives. I will plot both the analytical and automatic differentiated results.

%matplotlib inline import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # results from AD alpha = np.linspace(0.01, 1) # The AD derivative function is not vectorized, so we use this list comprehension. dphidalpha = [adphi(a) for a in alpha] def analytical_dphi(alpha): return -1 / (1 + alpha**2) plt.plot(alpha, analytical_dphi(alpha), label='analytical') plt.plot(alpha, dphidalpha, 'r--', label='AD') plt.xlabel(r'$\alpha$') plt.ylabel(r'$frac{d\phi}{d\alpha}$') plt.legend()

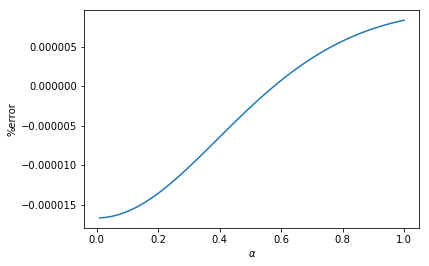

Visually, these are indistinguishable from each other. We can look at the errors too, and here we see they are negligible, and probably we can attribute them to the approximation we use for the integral, and not due to automatic differentiation.

perr = (analytical_dphi(alpha) - dphidalpha) / analytical_dphi(alpha) * 100 plt.plot(alpha, perr, label='analytical') plt.xlabel(r'$\alpha$') plt.ylabel('%error')

2 Example 2

In example 2 there is this function, which has variable limits:

\(f(x) = \int_{\sin x}^{\cos x} \cosh t^2 dt\)

What is \(f'(x)\) here? It can be derived with some effort and it is:

\(f'(x) = -\cosh(\cos^2 x) \sin x - \cosh(\sin^2 x) \cos x\)

This function was kind of fun to code up, I hadn't thought about how to represent variable limits, but here it is.

def f(x): a = np.sin(x) b = np.cos(x) t = np.linspace(a, b, 1000) y = np.cosh(t**2) return trapz(y, t) # Here is our derivative! dfdx = grad(f, 0)

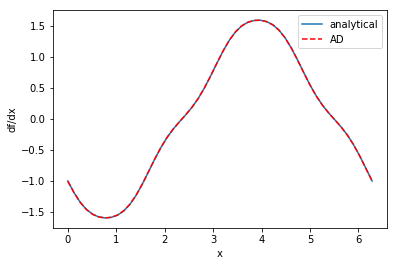

Here is a graphical comparison of the two:

x = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi) analytical = -np.cosh(np.cos(x)**2) * np.sin(x) - \ np.cosh(np.sin(x)**2) * np.cos(x) ad = [dfdx(_x) for _x in x] plt.plot(x, analytical, label='analytical') plt.plot(x, ad, 'r--', label='AD') plt.xlabel('x') plt.ylabel('df/dx') plt.legend()

These are once again indistinguishable.

3 Summary

These are amazing results to me. Before trying it, I would not have thought it would be so easy to evaluate the derivative of these functions. These work of course because all the operations involved in computing the integral are differentiable and defined in autograd. It certainly opens the door to all kinds of new approaches to solving engineering problems that need the derivatives for various purposes like optimization, sensitivity analysis, etc.

Copyright (C) 2018 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.

Org-mode version = 9.1.13