Computing a pipe diameter

Posted February 12, 2013 at 09:00 AM | categories: nonlinear algebra | tags: fluids

Updated March 06, 2013 at 04:38 PM

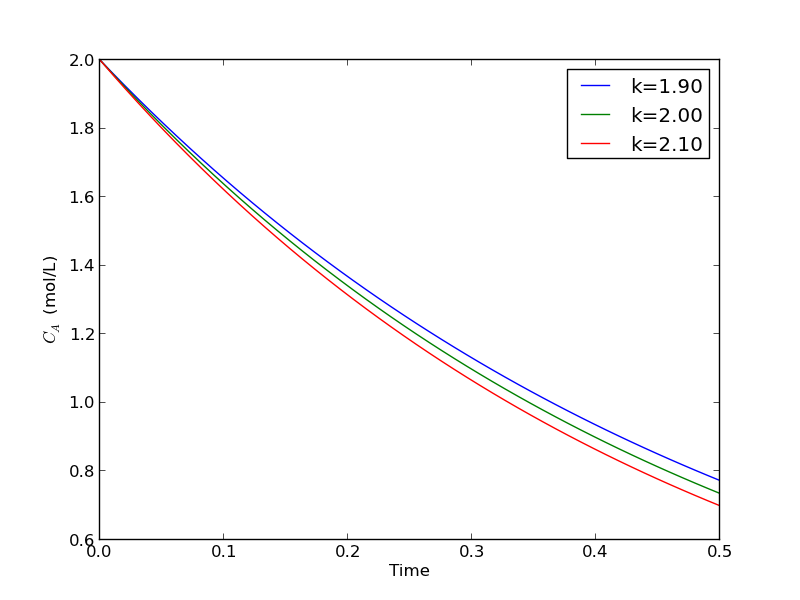

Matlab post A heat exchanger must handle 2.5 L/s of water through a smooth pipe with length of 100 m. The pressure drop cannot exceed 103 kPa at 25 degC. Compute the minimum pipe diameter required for this application.

Adapted from problem 8.8 in Problem solving in chemical and Biochemical Engineering with Polymath, Excel, and Matlab. page 303.

We need to estimate the Fanning friction factor for these conditions so we can estimate the frictional losses that result in a pressure drop for a uniform, circular pipe. The frictional forces are given by \(F_f = 2f_F \frac{\Delta L v^2}{D}\), and the corresponding pressure drop is given by \(\Delta P = \rho F_f\). In these equations, \(\rho\) is the fluid density, \(v\) is the fluid velocity, \(D\) is the pipe diameter, and \(f_F\) is the Fanning friction factor. The average fluid velocity is given by \(v = \frac{q}{\pi D^2/4}\).

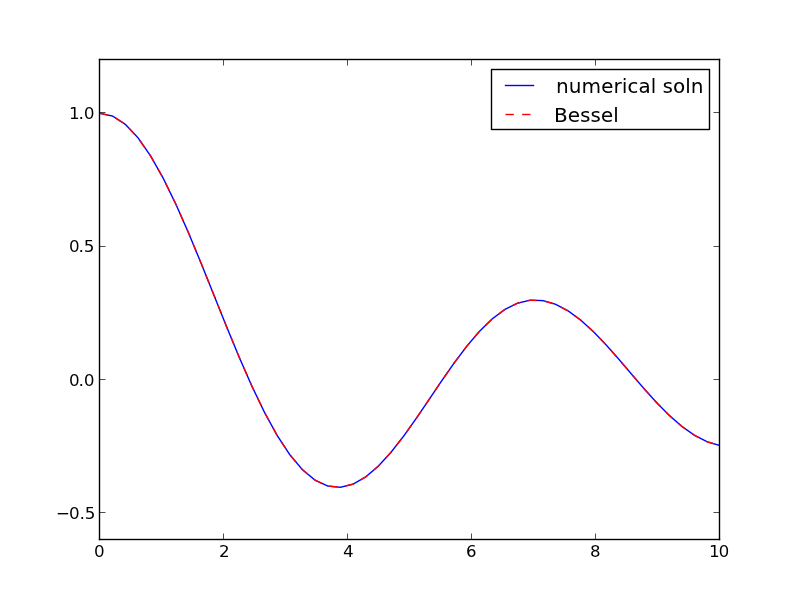

For laminar flow, we estimate \(f_F = 16/Re\), which is a linear equation, and for turbulent flow (\(Re > 2100\)) we have the implicit equation \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{f_F}}=4.0 \log(Re \sqrt{f_F})-0.4\). Of course, we define \(Re = \frac{D v\rho}{\mu}\) where \(\mu\) is the viscosity of the fluid.

It is known that \(\rho(T) = 46.048 + 9.418 T -0.0329 T^2 +4.882\times10^{-5}-2.895\times10^{-8}T^4\) and \(\mu = \exp\left({-10.547 + \frac{541.69}{T-144.53}}\right)\) where \(\rho\) is in kg/m^3 and \(\mu\) is in kg/(m*s).

The aim is to find \(D\) that solves: \(\Delta p = \rho 2 f_F \frac{\Delta L v^2}{D}\). This is a nonlinear equation in \(D\), since D affects the fluid velocity, the Re, and the Fanning friction factor. Here is the solution

import numpy as np from scipy.optimize import fsolve import matplotlib.pyplot as plt T = 25 + 273.15 Q = 2.5e-3 # m^3/s deltaP = 103000 # Pa deltaL = 100 # m #Note these correlations expect dimensionless T, where the magnitude # of T is in K def rho(T): return 46.048 + 9.418 * T -0.0329 * T**2 +4.882e-5 * T**3 - 2.895e-8 * T**4 def mu(T): return np.exp(-10.547 + 541.69 / (T - 144.53)) def fanning_friction_factor_(Re): if Re < 2100: raise Exception('Flow is probably not turbulent, so this correlation is not appropriate.') # solve the Nikuradse correlation to get the friction factor def fz(f): return 1.0/np.sqrt(f) - (4.0*np.log10(Re*np.sqrt(f))-0.4) sol, = fsolve(fz, 0.01) return sol fanning_friction_factor = np.vectorize(fanning_friction_factor_) Re = np.linspace(2200, 9000) f = fanning_friction_factor(Re) plt.plot(Re, f) plt.xlabel('Re') plt.ylabel('fanning friction factor') # You can see why we use 0.01 as an initial guess for solving for the # Fanning friction factor; it falls in the middle of ranges possible # for these Re numbers. plt.savefig('images/pipe-diameter-1.png') def objective(D): v = Q / (np.pi * D**2 / 4) Re = D * v * rho(T) / mu(T) fF = fanning_friction_factor(Re) return deltaP - 2 * fF * rho(T) * deltaL * v**2 / D D, = fsolve(objective, 0.04) print('The minimum pipe diameter is {0} m\n'.format(D))

The minimum pipe diameter is 0.0389653369531 m

Any pipe diameter smaller than that value will result in a larger pressure drop at the same volumetric flow rate, or a smaller volumetric flowrate at the same pressure drop. Either way, it will not meet the design specification.

Copyright (C) 2013 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.