Matlab post

Random numbers are used in a variety of simulation methods, most notably Monte Carlo simulations. In another later example, we will see how we can use random numbers for error propagation analysis. First, we discuss two types of pseudorandom numbers we can use in python: uniformly distributed and normally distributed numbers.

Say you are the gambling type, and bet your friend $5 the next random number will be greater than 0.49. Let us ask Python to roll the random number generator for us.

import numpy as np

n = np.random.uniform()

print 'n = {0}'.format(n)

if n > 0.49:

print 'You win!'

else:

print 'you lose.'

n = 0.381896986693

you lose.

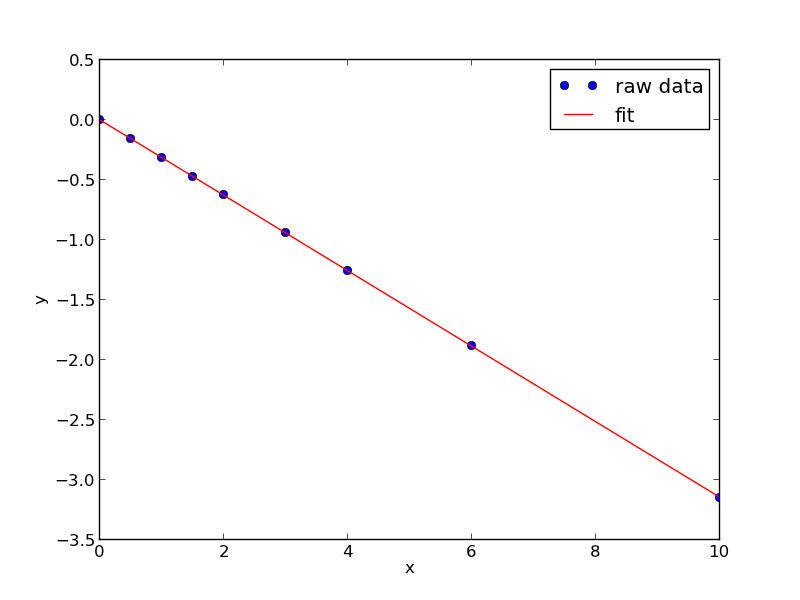

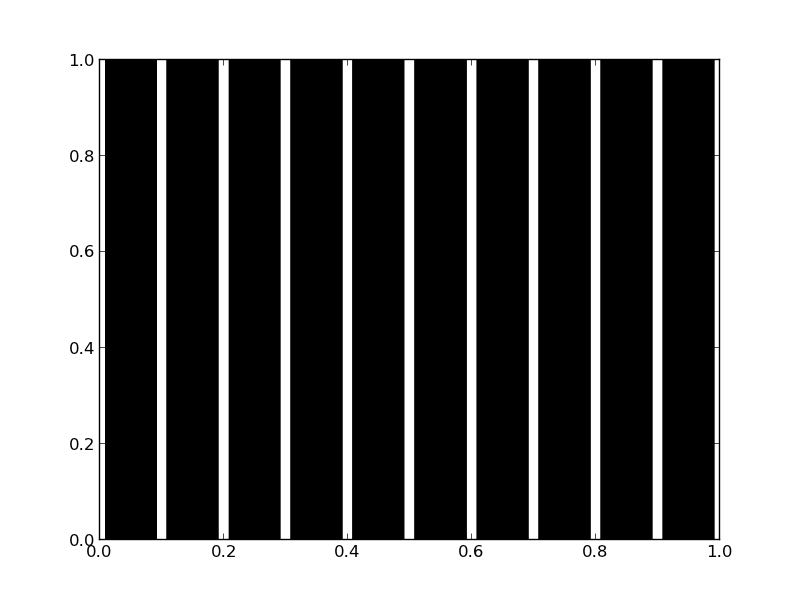

The odds of you winning the last bet are slightly stacked in your favor. There is only a 49% chance your friend wins, but a 51% chance that you win. Lets play the game a lot of times times and see how many times you win, and your friend wins. First, lets generate a bunch of numbers and look at the distribution with a histogram.

import numpy as np

N = 10000

games = np.random.uniform(size=(1,N))

wins = np.sum(games > 0.49)

losses = N - wins

print 'You won {0} times ({1:%})'.format(wins, float(wins) / N)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

count, bins, ignored = plt.hist(games)

plt.savefig('images/random-thoughts-1.png')

You won 5090 times (50.900000%)

As you can see you win slightly more than you lost.

It is possible to get random integers. Here are a few examples of getting a random integer between 1 and 100. You might do this to get random indices of a list, for example.

import numpy as np

print np.random.random_integers(1, 100)

print np.random.random_integers(1, 100, 3)

print np.random.random_integers(1, 100, (2,2))

96

[ 95 49 100]

[[69 54]

[41 93]]

The normal distribution is defined by \(f(x)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \exp (-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2})\) where \(\mu\) is the mean value, and \(\sigma\) is the standard deviation. In the standard distribution, \(\mu=0\) and \(\sigma=1\).

import numpy as np

mu = 1

sigma = 0.5

print np.random.normal(mu, sigma)

print np.random.normal(mu, sigma, 2)

1.04225842065

[ 0.58105204 0.64853157]

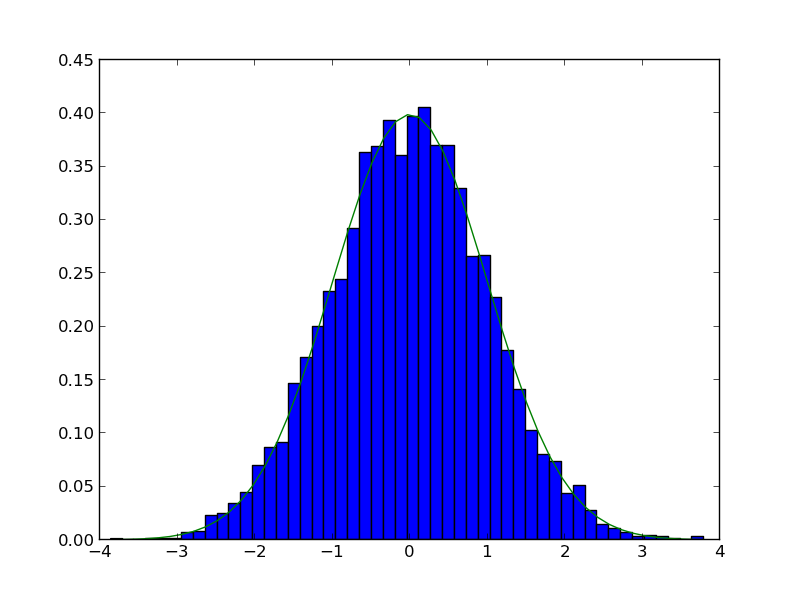

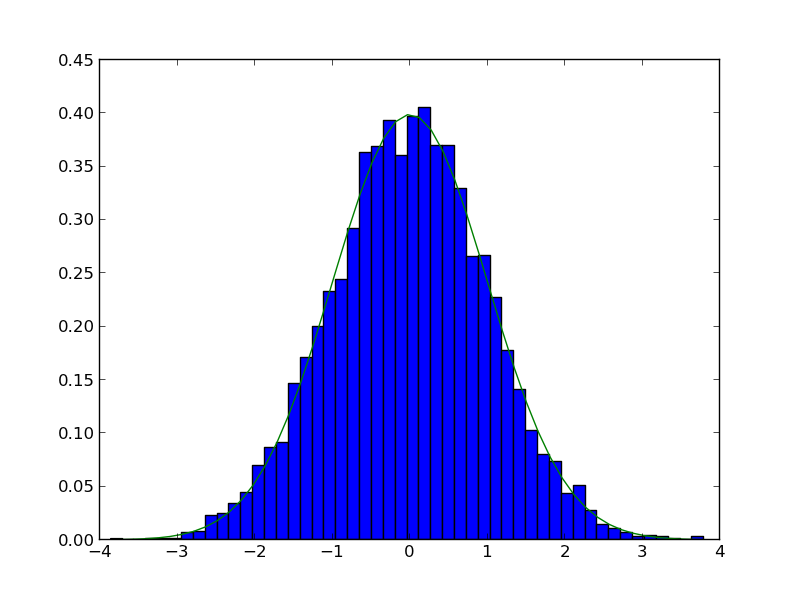

Let us compare the sampled distribution to the analytical distribution. We generate a large set of samples, and calculate the probability of getting each value using the matplotlib.pyplot.hist command.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

mu = 0; sigma = 1

N = 5000

samples = np.random.normal(mu, sigma, N)

counts, bins, ignored = plt.hist(samples, 50, normed=True)

plt.plot(bins, 1.0/np.sqrt(2 * np.pi * sigma**2)*np.exp(-((bins - mu)**2)/(2*sigma**2)))

plt.savefig('images/random-thoughts-2.png')

What fraction of points lie between plus and minus one standard deviation of the mean?

samples >= mu-sigma will return a vector of ones where the inequality is true, and zeros where it is not. (samples >= mu-sigma) & (samples <= mu+sigma) will return a vector of ones where there is a one in both vectors, and a zero where there is not. In other words, a vector where both inequalities are true. Finally, we can sum the vector to get the number of elements where the two inequalities are true, and finally normalize by the total number of samples to get the fraction of samples that are greater than -sigma and less than sigma.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

mu = 0; sigma = 1

N = 5000

samples = np.random.normal(mu, sigma, N)

a = np.sum((samples >= (mu - sigma)) & (samples <= (mu + sigma))) / float(N)

b = np.sum((samples >= (mu - 2*sigma)) & (samples <= (mu + 2*sigma))) / float(N)

print '{0:%} of samples are within +- standard deviations of the mean'.format(a)

print '{0:%} of samples are within +- 2standard deviations of the mean'.format(b)

67.500000% of samples are within +- standard deviations of the mean

95.580000% of samples are within +- 2standard deviations of the mean

1 Summary

We only considered the numpy.random functions here, and not all of them. There are many distributions of random numbers to choose from. There are also random numbers in the python random module. Remember these are only pseudorandom numbers, but they are still useful for many applications.

Copyright (C) 2013 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.

org-mode source