Water gas shift equilibria via the NIST Webbook

Posted February 01, 2013 at 09:00 AM | categories: nonlinear algebra | tags:

Updated February 27, 2013 at 02:46 PM

The NIST webbook provides parameterized models of the enthalpy, entropy and heat capacity of many molecules. In this example, we will examine how to use these to compute the equilibrium constant for the water gas shift reaction \(CO + H_2O \rightleftharpoons CO_2 + H_2\) in the temperature range of 500K to 1000K.

Parameters are provided for:

Cp = heat capacity (J/mol*K) H = standard enthalpy (kJ/mol) S = standard entropy (J/mol*K)

with models in the form: \(Cp^\circ = A + B*t + C*t^2 + D*t^3 + E/t^2\)

\(H^\circ - H^\circ_{298.15}= A*t + B*t^2/2 + C*t^3/3 + D*t^4/4 - E/t + F - H\)

\(S^\circ = A*ln(t) + B*t + C*t^2/2 + D*t^3/3 - E/(2*t^2) + G\)

where \(t=T/1000\), and \(T\) is the temperature in Kelvin. We can use this data to calculate equilibrium constants in the following manner. First, we have heats of formation at standard state for each compound; for elements, these are zero by definition, and for non-elements, they have values available from the NIST webbook. There are also values for the absolute entropy at standard state. Then, we have an expression for the change in enthalpy from standard state as defined above, as well as the absolute entropy. From these we can derive the reaction enthalpy, free energy and entropy at standard state, as well as at other temperatures.

We will examine the water gas shift enthalpy, free energy and equilibrium constant from 500K to 1000K, and finally compute the equilibrium composition of a gas feed containing 5 atm of CO and H_2 at 1000K.

import numpy as np T = np.linspace(500,1000) # degrees K t = T/1000;

1 hydrogen

\url{http://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C1333740&Units=SI&Mask=1#Thermo-Gas}

# T = 298-1000K valid temperature range A = 33.066178 B = -11.363417 C = 11.432816 D = -2.772874 E = -0.158558 F = -9.980797 G = 172.707974 H = 0.0 Hf_29815_H2 = 0.0 # kJ/mol S_29815_H2 = 130.68 # J/mol/K dH_H2 = A*t + B*t**2/2 + C*t**3/3 + D*t**4/4 - E/t + F - H; S_H2 = (A*np.log(t) + B*t + C*t**2/2 + D*t**3/3 - E/(2*t**2) + G);

2 H_{2}O

\url{http://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C7732185&Units=SI&Mask=1#Thermo-Gas}

Note these parameters limit the temperature range we can examine, as these parameters are not valid below 500K. There is another set of parameters for lower temperatures, but we do not consider them here.

# 500-1700 K valid temperature range A = 30.09200 B = 6.832514 C = 6.793435 D = -2.534480 E = 0.082139 F = -250.8810 G = 223.3967 H = -241.8264 Hf_29815_H2O = -241.83 #this is Hf. S_29815_H2O = 188.84 dH_H2O = A*t + B*t**2/2 + C*t**3/3 + D*t**4/4 - E/t + F - H; S_H2O = (A*np.log(t) + B*t + C*t**2/2 + D*t**3/3 - E/(2*t**2) + G);

3 CO

\url{http://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C630080&Units=SI&Mask=1#Thermo-Gas}

# 298. - 1300K valid temperature range A = 25.56759 B = 6.096130 C = 4.054656 D = -2.671301 E = 0.131021 F = -118.0089 G = 227.3665 H = -110.5271 Hf_29815_CO = -110.53 #this is Hf kJ/mol. S_29815_CO = 197.66 dH_CO = A*t + B*t**2/2 + C*t**3/3 + D*t**4/4 - E/t + F - H; S_CO = (A*np.log(t) + B*t + C*t**2/2 + D*t**3/3 - E/(2*t**2) + G);

4 CO_{2}

\url{http://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C124389&Units=SI&Mask=1#Thermo-Gas}

# 298. - 1200.K valid temperature range A = 24.99735 B = 55.18696 C = -33.69137 D = 7.948387 E = -0.136638 F = -403.6075 G = 228.2431 H = -393.5224 Hf_29815_CO2 = -393.51 # this is Hf. S_29815_CO2 = 213.79 dH_CO2 = A*t + B*t**2/2 + C*t**3/3 + D*t**4/4 - E/t + F - H; S_CO2 = (A*np.log(t) + B*t + C*t**2/2 + D*t**3/3 - E/(2*t**2) + G);

5 Standard state heat of reaction

We compute the enthalpy and free energy of reaction at 298.15 K for the following reaction \(CO + H2O \rightleftharpoons H2 + CO2\).

Hrxn_29815 = Hf_29815_CO2 + Hf_29815_H2 - Hf_29815_CO - Hf_29815_H2O; Srxn_29815 = S_29815_CO2 + S_29815_H2 - S_29815_CO - S_29815_H2O; Grxn_29815 = Hrxn_29815 - 298.15*(Srxn_29815)/1000; print('deltaH = {0:1.2f}'.format(Hrxn_29815)) print('deltaG = {0:1.2f}'.format(Grxn_29815))

>>> >>> >>> deltaH = -41.15 deltaG = -28.62

6 Non-standard state \(\Delta H\) and \(\Delta G\)

We have to correct for temperature change away from standard state. We only correct the enthalpy for this temperature change. The correction looks like this:

$$ \Delta H_{rxn}(T) = \Delta H_{rxn}(T_{ref}) + \sum_i \nu_i (H_i(T)-H_i(T_{ref}))$$

Where \(\nu_i\) are the stoichiometric coefficients of each species, with appropriate sign for reactants and products, and \((H_i(T)-H_i(T_{ref})\) is precisely what is calculated for each species with the equations

The entropy is on an absolute scale, so we directly calculate entropy at each temperature. Recall that H is in kJ/mol and S is in J/mol/K, so we divide S by 1000 to make the units match.

Hrxn = Hrxn_29815 + dH_CO2 + dH_H2 - dH_CO - dH_H2O Grxn = Hrxn - T*(S_CO2 + S_H2 - S_CO - S_H2O)/1000

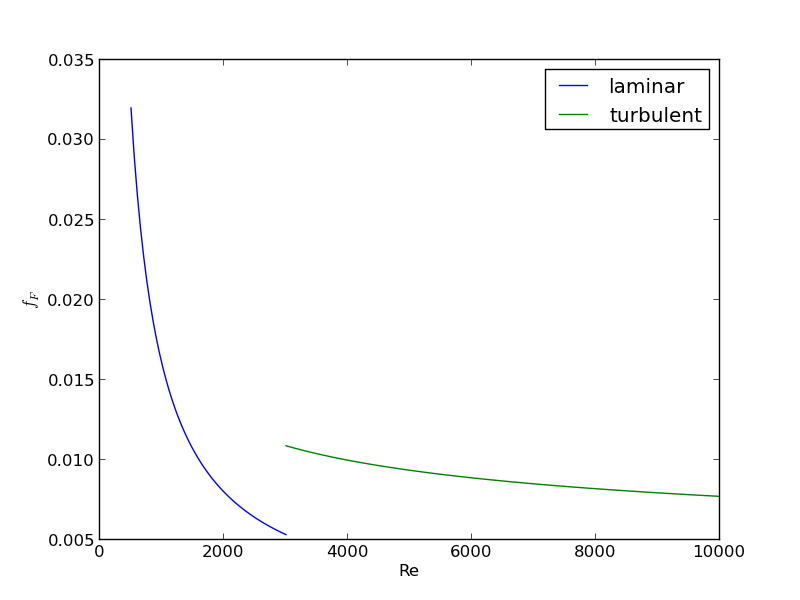

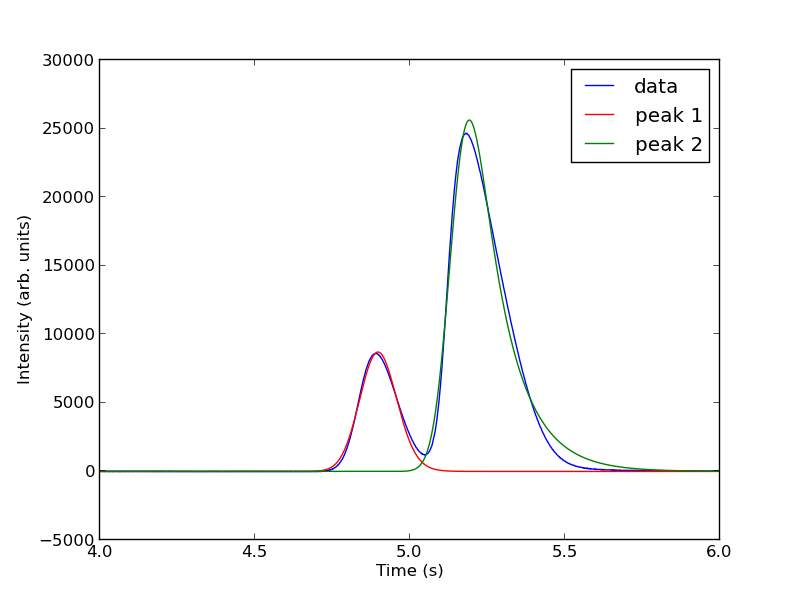

7 Plot how the \(\Delta G\) varies with temperature

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt plt.figure(); plt.clf() plt.plot(T,Grxn, label='$\Delta G_{rxn}$') plt.plot(T,Hrxn, label='$\Delta H_{rxn}$') plt.xlabel('Temperature (K)') plt.ylabel('(kJ/mol)') plt.legend( loc='best') plt.savefig('images/wgs-nist-1.png')

<matplotlib.figure.Figure object at 0x04199CF0> [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D object at 0x0429BF30>] [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D object at 0x0427DFB0>] <matplotlib.text.Text object at 0x041B79F0> <matplotlib.text.Text object at 0x040CEF70> <matplotlib.legend.Legend object at 0x043CB5F0>

Over this temperature range the reaction is exothermic, although near 1000K it is just barely exothermic. At higher temperatures we expect the reaction to become endothermic.

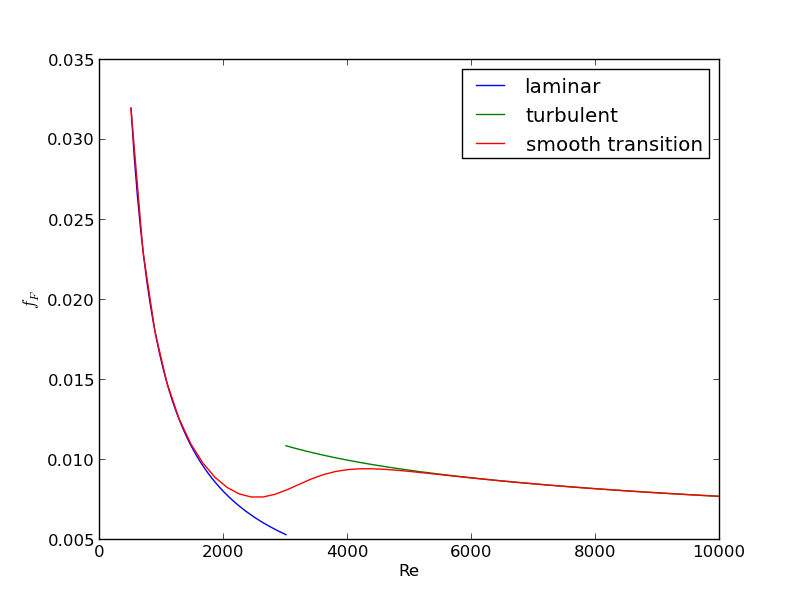

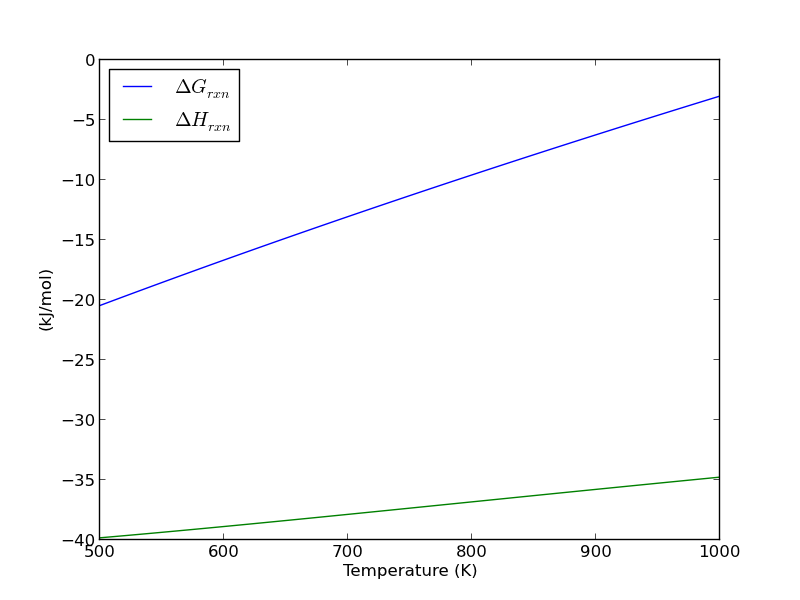

8 Equilibrium constant calculation

Note the equilibrium constant starts out high, i.e. strongly favoring the formation of products, but drops very quicky with increasing temperature.

R = 8.314e-3 # kJ/mol/K K = np.exp(-Grxn/R/T); plt.figure() plt.plot(T,K) plt.xlim([500, 1000]) plt.xlabel('Temperature (K)') plt.ylabel('Equilibrium constant') plt.savefig('images/wgs-nist-2.png')

>>> >>> <matplotlib.figure.Figure object at 0x044DBE90> [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D object at 0x045A53F0>] (500, 1000) <matplotlib.text.Text object at 0x04577470> <matplotlib.text.Text object at 0x0457F410>

9 Equilibrium yield of WGS

Now let us suppose we have a reactor with a feed of H_2O and CO at 10atm at 1000K. What is the equilibrium yield of H_2? Let \(\epsilon\) be the extent of reaction, so that \(F_i = F_{i,0} + \nu_i \epsilon\). For reactants, \(\nu_i\) is negative, and for products, \(\nu_i\) is positive. We have to solve for the extent of reaction that satisfies the equilibrium condition.

from scipy.interpolate import interp1d from scipy.optimize import fsolve # # A = CO # B = H2O # C = H2 # D = CO2 Pa0 = 5; Pb0 = 5; Pc0 = 0; Pd0 = 0; # pressure in atm R = 0.082; Temperature = 1000; # we can estimate the equilibrium like this. We could also calculate it # using the equations above, but we would have to evaluate each term. Above # we simply computed a vector of enthalpies, entropies, etc... Here we interpolate K_func = interp1d(T,K); K_Temperature = K_func(1000) # If we let X be fractional conversion then we have $C_A = C_{A0}(1-X)$, # $C_B = C_{B0}-C_{A0}X$, $C_C = C_{C0}+C_{A0}X$, and $C_D = # C_{D0}+C_{A0}X$. We also have $K(T) = (C_C C_D)/(C_A C_B)$, which finally # reduces to $0 = K(T) - Xeq^2/(1-Xeq)^2$ under these conditions. def f(X): return K_Temperature - X**2/(1-X)**2; x0 = 0.5 Xeq, = fsolve(f, x0) print('The equilibrium conversion for these feed conditions is: {0:1.2f}'.format(Xeq))

>>> >>> ... ... ... ... ... >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> ... ... ... >>> >>> >>> >>> ... ... ... ... >>> ... ... >>> >>> >>> 0.54504291144 The equilibrium conversion for these feed conditions is: 0.55

10 Compute gas phase pressures of each species

Since there is no change in moles for this reaction, we can directly calculation the pressures from the equilibrium conversion and the initial pressure of gases. you can see there is a slightly higher pressure of H_2 and CO_2 than the reactants, consistent with the equilibrium constant of about 1.44 at 1000K. At a lower temperature there would be a much higher yield of the products. For example, at 550K the equilibrium constant is about 58, and the pressure of H_2 is 4.4 atm due to a much higher equilibrium conversion of 0.88.

P_CO = Pa0*(1-Xeq)

P_H2O = Pa0*(1-Xeq)

P_H2 = Pa0*Xeq

P_CO2 = Pa0*Xeq

print P_CO,P_H2O, P_H2, P_CO2

>>> >>> >>> >>> 2.2747854428 2.2747854428 2.7252145572 2.7252145572

11 Compare the equilibrium constants

We can compare the equilibrium constant from the Gibbs free energy and the one from the ratio of pressures. They should be the same!

print K_Temperature print (P_CO2*P_H2)/(P_CO*P_H2O)

1.43522674762 1.43522674762

They are the same.

12 Summary

The NIST Webbook provides a plethora of data for computing thermodynamic properties. It is a little tedious to enter it all into Matlab, and a little tricky to use the data to estimate temperature dependent reaction energies. A limitation of the Webbook is that it does not tell you have the thermodynamic properties change with pressure. Luckily, those changes tend to be small.

I noticed a different behavior in interpolation between scipy.interpolate.interp1d and Matlab's interp1. The scipy function returns an interpolating function, whereas the Matlab function directly interpolates new values, and returns the actual interpolated data.

Copyright (C) 2013 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.