Plane poiseuelle flow solved by finite difference

Posted February 14, 2013 at 09:00 AM | categories: bvp | tags: fluids

Updated March 06, 2013 at 06:32 PM

Adapted from http://www.physics.arizona.edu/~restrepo/475B/Notes/sourcehtml/node24.html

We want to solve a linear boundary value problem of the form: y'' = p(x)y' + q(x)y + r(x) with boundary conditions y(x1) = alpha and y(x2) = beta.

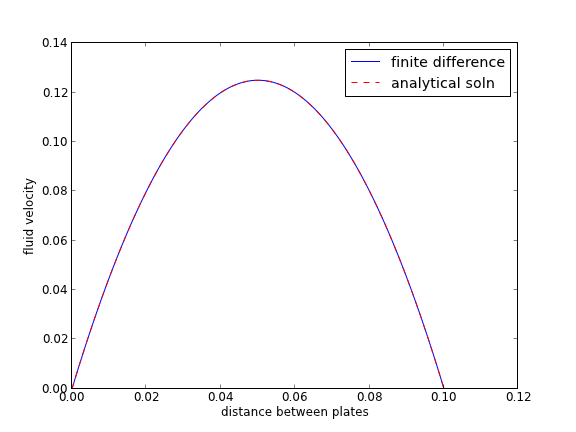

For this example, we solve the plane poiseuille flow problem using a finite difference approach. An advantage of the approach we use here is we do not have to rewrite the second order ODE as a set of coupled first order ODEs, nor do we have to provide guesses for the solution. We do, however, have to discretize the derivatives and formulate a linear algebra problem.

we want to solve u'' = 1/mu*DPDX with u(0)=0 and u(0.1)=0. for this problem we let the plate separation be d=0.1, the viscosity \(\mu = 1\), and \(\frac{\Delta P}{\Delta x} = -100\).

The idea behind the finite difference method is to approximate the derivatives by finite differences on a grid. See here for details. By discretizing the ODE, we arrive at a set of linear algebra equations of the form \(A y = b\), where \(A\) and \(b\) are defined as follows.

\[A = \left [ \begin{array}{ccccc} % 2 + h^2 q_1 & -1 + \frac{h}{2} p_1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 - \frac{h}{2} p_2 & 2 + h^2 q_2 & -1 + \frac{h}{2} p_2 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \ddots & \ddots & \ddots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 - \frac{h}{2} p_{N-1} & 2 + h^2 q_{N-1} & -1 + \frac{h}{2} p_{N-1} \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 - \frac{h}{2} p_N & 2 + h^2 q_N \end{array} \right ] \]

\[ y = \left [ \begin{array}{c} y_i \\ \vdots \\ y_N \end{array} \right ] \]

\[ b = \left [ \begin{array}{c} -h^2 r_1 + ( 1 + \frac{h}{2} p_1) \alpha \\ -h^2 r_2 \\ \vdots \\ -h^2 r_{N-1} \\ -h^2 r_N + (1 - \frac{h}{2} p_N) \beta \end{array} \right] \]

import numpy as np # we use the notation for y'' = p(x)y' + q(x)y + r(x) def p(x): return 0 def q(x): return 0 def r(x): return -100 #we use the notation y(x1) = alpha and y(x2) = beta x1 = 0; alpha = 0.0 x2 = 0.1; beta = 0.0 npoints = 100 # compute interval width h = (x2-x1)/npoints; # preallocate and shape the b vector and A-matrix b = np.zeros((npoints - 1, 1)); A = np.zeros((npoints - 1, npoints - 1)); X = np.zeros((npoints - 1, 1)); #now we populate the A-matrix and b vector elements for i in range(npoints - 1): X[i,0] = x1 + (i + 1) * h # get the value of the BVP Odes at this x pi = p(X[i]) qi = q(X[i]) ri = r(X[i]) if i == 0: # first boundary condition b[i] = -h**2 * ri + (1 + h / 2 * pi)*alpha; elif i == npoints - 1: # second boundary condition b[i] = -h**2 * ri + (1 - h / 2 * pi)*beta; else: b[i] = -h**2 * ri # intermediate points for j in range(npoints - 1): if j == i: # the diagonal A[i,j] = 2 + h**2 * qi elif j == i - 1: # left of the diagonal A[i,j] = -1 - h / 2 * pi elif j == i + 1: # right of the diagonal A[i,j] = -1 + h / 2 * pi else: A[i,j] = 0 # off the tri-diagonal # solve the equations A*y = b for Y Y = np.linalg.solve(A,b) x = np.hstack([x1, X[:,0], x2]) y = np.hstack([alpha, Y[:,0], beta]) import matplotlib.pyplot as plt plt.plot(x, y) mu = 1 d = 0.1 x = np.linspace(0,0.1); Pdrop = -100 # this is DeltaP/Deltax u = -(Pdrop) * d**2 / 2.0 / mu * (x / d - (x / d)**2) plt.plot(x,u,'r--') plt.xlabel('distance between plates') plt.ylabel('fluid velocity') plt.legend(('finite difference', 'analytical soln')) plt.savefig('images/pp-bvp-fd.png') plt.show()

You can see excellent agreement here between the numerical and analytical solution.

Copyright (C) 2013 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.

with boundary conditions

with boundary conditions  and

and  at

at  . We convert this equation to a system of first order ODEs by letting

. We convert this equation to a system of first order ODEs by letting  . Then, our two equations become:

. Then, our two equations become:

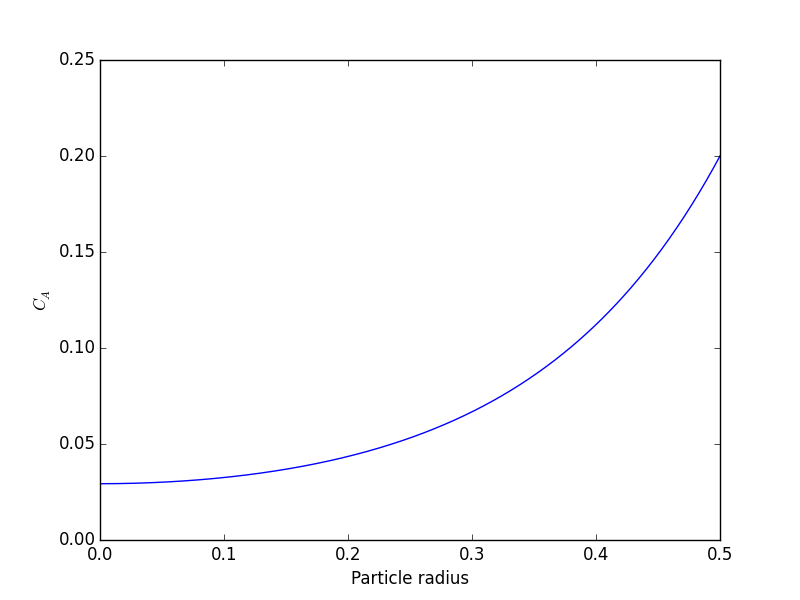

) at r=0 and Ca(R) = CAs, which makes this a boundary value problem. We use the shooting method here, and guess what Ca(0) is and iterate the guess to get Ca(R) = CAs.

) at r=0 and Ca(R) = CAs, which makes this a boundary value problem. We use the shooting method here, and guess what Ca(0) is and iterate the guess to get Ca(R) = CAs.

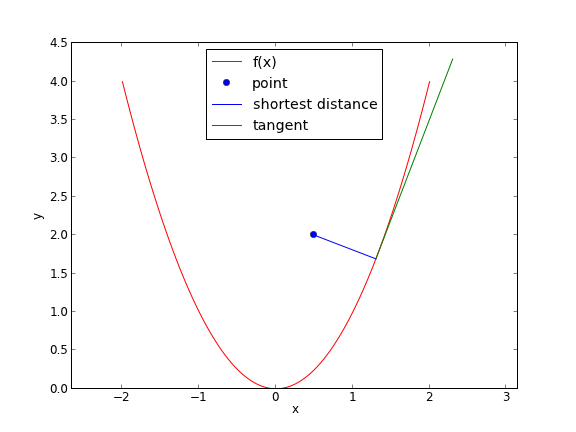

and the derivative of the bottom is 1. So, we have

and the derivative of the bottom is 1. So, we have

at

at