Matlab post

Adapted from Perry's Chemical Engineers Handbook, 6th edition 2-63.

We seek the solution to the following nonlinear equations:

\(2 + x + y - x^2 + 8 x y + y^3 = 0\)

\(1 + 2x - 3y + x^2 + xy - y e^x = 0\)

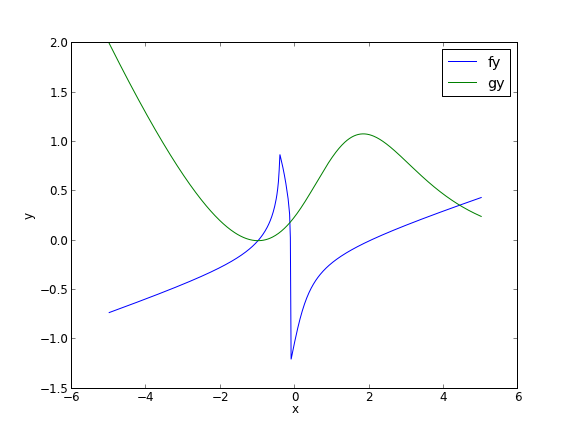

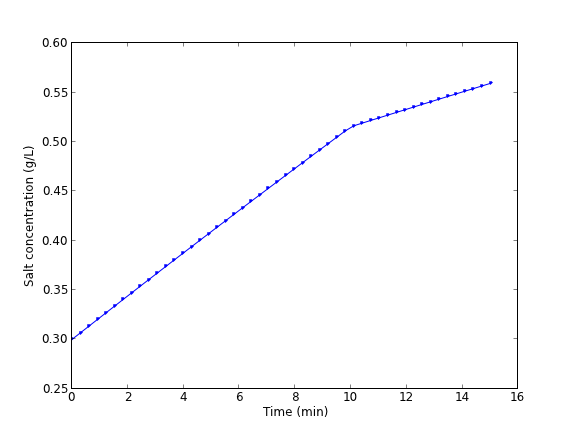

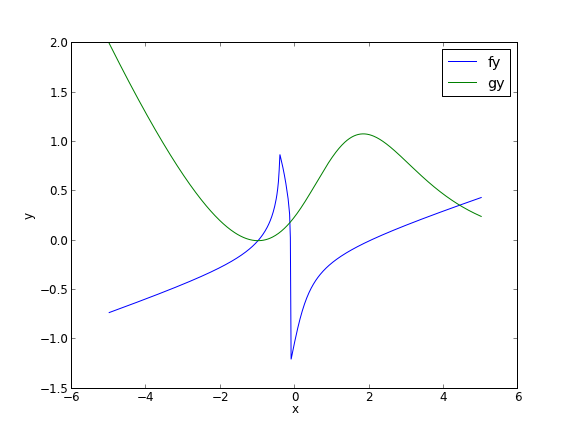

In principle this is easy, we simply need some initial guesses and a nonlinear solver. The challenge here is what would you guess? There could be many solutions. The equations are implicit, so it is not easy to graph them, but let us give it a shot, starting on the x range -5 to 5. The idea is set a value for x, and then solve for y in each equation.

import numpy as np

from scipy.optimize import fsolve

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def f(x, y):

return 2 + x + y - x**2 + 8*x*y + y**3;

def g(x, y):

return 1 + 2*x - 3*y + x**2 + x*y - y*np.exp(x)

x = np.linspace(-5, 5, 500)

@np.vectorize

def fy(x):

x0 = 0.0

def tmp(y):

return f(x, y)

y1, = fsolve(tmp, x0)

return y1

@np.vectorize

def gy(x):

x0 = 0.0

def tmp(y):

return g(x, y)

y1, = fsolve(tmp, x0)

return y1

plt.plot(x, fy(x), x, gy(x))

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('y')

plt.legend(['fy', 'gy'])

plt.savefig('images/continuation-1.png')

>>> >>> >>> >>> ... ... >>> ... ... >>> >>> >>> ... ... ... ... ... ... ... >>> ... ... ... ... ... ... ... >>> >>> /opt/kitchingroup/enthought/epd-7.3-2-rh5-x86_64/lib/python2.7/site-packages/scipy/optimize/minpack.py:152: RuntimeWarning: The iteration is not making good progress, as measured by the

improvement from the last ten iterations.

warnings.warn(msg, RuntimeWarning)

/opt/kitchingroup/enthought/epd-7.3-2-rh5-x86_64/lib/python2.7/site-packages/scipy/optimize/minpack.py:152: RuntimeWarning: The iteration is not making good progress, as measured by the

improvement from the last five Jacobian evaluations.

warnings.warn(msg, RuntimeWarning)

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D object at 0x1a0c4990>, <matplotlib.lines.Line2D object at 0x1a0c4a90>]

<matplotlib.text.Text object at 0x19d5e390>

<matplotlib.text.Text object at 0x19d61d90>

<matplotlib.legend.Legend object at 0x189df850>

You can see there is a solution near x = -1, y = 0, because both functions equal zero there. We can even use that guess with fsolve. It is disappointly easy! But, keep in mind that in 3 or more dimensions, you cannot perform this visualization, and another method could be required.

def func(X):

x,y = X

return [f(x, y), g(x, y)]

print fsolve(func, [-2, -2])

... ... >>> [ -1.00000000e+00 1.28730858e-15]

We explore a method that bypasses this problem today. The principle is to introduce a new variable, \(\lambda\), which will vary from 0 to 1. at \(\lambda=0\) we will have a simpler equation, preferrably a linear one, which can be easily solved, or which can be analytically solved. At \(\lambda=1\), we have the original equations. Then, we create a system of differential equations that start at the easy solution, and integrate from \(\lambda=0\) to \(\lambda=1\), to recover the final solution.

We rewrite the equations as:

\(f(x,y) = (2 + x + y) + \lambda(- x^2 + 8 x y + y^3) = 0\)

\(g(x,y) = (1 + 2x - 3y) + \lambda(x^2 + xy - y e^x) = 0\)

Now, at \(\lambda=0\) we have the simple linear equations:

\(x + y = -2\)

\(2x - 3y = -1\)

These equations are trivial to solve:

x0 = np.linalg.solve([[1., 1.], [2., -3.]],[ -2, -1])

print x0

[-1.4 -0.6]

We form the system of ODEs by differentiating the new equations with respect to \(\lambda\). Why do we do that? The solution, (x,y) will be a function of \(\lambda\). From calculus, you can show that:

\(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \lambda}+\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\frac{\partial y}{\partial \lambda}=-\frac{\partial f}{\partial \lambda}\)

\(\frac{\partial g}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \lambda}+\frac{\partial g}{\partial y}\frac{\partial y}{\partial \lambda}=-\frac{\partial g}{\partial \lambda}\)

Now, solve this for \(\frac{\partial x}{\partial \lambda}\) and \(\frac{\partial y}{\partial \lambda}\). You can use Cramer's rule to solve for these to yield:

\begin{eqnarray} \

\frac{\partial x}{\partial \lambda} &=& \frac{\partial f/\partial y \partial g/\partial \lambda - \partial f/\partial \lambda \partial g/\partial y}{\partial f/\partial x \partial g/\partial y - \partial f/\partial y \partial g/\partial x } \\\\

\frac{\partial y}{\partial \lambda} &=& \frac{\partial f/\partial \lambda \partial g/\partial x - \partial f/\partial x \partial g/\partial \lambda}{\partial f/\partial x \partial g/\partial y - \partial f/\partial y \partial g/\partial x } \end{eqnarray}

For this set of equations:

\begin{eqnarray} \

\partial f/\partial x &=& 1 - 2\lambda x + 8\lambda y \\\\

\partial f/\partial y &=& 1 + 8 \lambda x + 3 \lambda y^2 \\\\

\partial g/\partial x &=& 2 + 2 \lambda x + \lambda y - \lambda y e^x\\\\

\partial g/\partial y &=& -3 + \lambda x - \lambda e^x

\end{eqnarray}

Now, we simply set up those two differential equations on \(\frac{\partial x}{\partial \lambda}\) and \(\frac{\partial y}{\partial \lambda}\), with the initial conditions at \(\lambda = 0\) which is the solution of the simpler linear equations, and integrate to \(\lambda = 1\), which is the final solution of the original equations!

def ode(X, LAMBDA):

x,y = X

pfpx = 1.0 - 2.0 * LAMBDA * x + 8 * LAMBDA * y

pfpy = 1.0 + 8.0 * LAMBDA * x + 3.0 * LAMBDA * y**2

pfpLAMBDA = -x**2 + 8.0 * x * y + y**3;

pgpx = 2. + 2. * LAMBDA * x + LAMBDA * y - LAMBDA * y * np.exp(x)

pgpy = -3. + LAMBDA * x - LAMBDA * np.exp(x)

pgpLAMBDA = x**2 + x * y - y * np.exp(x);

dxdLAMBDA = (pfpy * pgpLAMBDA - pfpLAMBDA * pgpy) / (pfpx * pgpy - pfpy * pgpx)

dydLAMBDA = (pfpLAMBDA * pgpx - pfpx * pgpLAMBDA) / (pfpx * pgpy - pfpy * pgpx)

dXdLAMBDA = [dxdLAMBDA, dydLAMBDA]

return dXdLAMBDA

from scipy.integrate import odeint

lambda_span = np.linspace(0, 1, 100)

X = odeint(ode, x0, lambda_span)

xsol, ysol = X[-1]

print 'The solution is at x={0:1.3f}, y={1:1.3f}'.format(xsol, ysol)

print f(xsol, ysol), g(xsol, ysol)

... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> The solution is at x=-1.000, y=0.000

-1.27746598808e-06 -1.15873819107e-06

You can see the solution is somewhat approximate; the true solution is x = -1, y = 0. The approximation could be improved by lowering the tolerance on the ODE solver. The functions evaluate to a small number, close to zero. You have to apply some judgment to determine if that is sufficiently accurate. For instance if the units on that answer are kilometers, but you need an answer accurate to a millimeter, this may not be accurate enough.

This is a fair amount of work to get a solution! The idea is to solve a simple problem, and then gradually turn on the hard part by the lambda parameter. What happens if there are multiple solutions? The answer you finally get will depend on your \(\lambda=0\) starting point, so it is possible to miss solutions this way. For problems with lots of variables, this would be a good approach if you can identify the easy problem.

Copyright (C) 2013 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.

org-mode source