A novel way to numerically estimate the derivative of a function - complex-step derivative approximation

Posted February 27, 2013 at 02:51 PM | categories: math | tags:

Updated July 09, 2013 at 08:53 PM

Adapted from http://biomedicalcomputationreview.org/2/3/8.pdf and http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=838250.838251

This posts introduces a novel way to numerically estimate the derivative of a function that does not involve finite difference schemes. Finite difference schemes are approximations to derivatives that become more and more accurate as the step size goes to zero, except that as the step size approaches the limits of machine accuracy, new errors can appear in the approximated results. In the references above, a new way to compute the derivative is presented that does not rely on differences!

The new way is: \(f'(x) = \rm{imag}(f(x + i\Delta x)/\Delta x)\) where the function \(f\) is evaluated in imaginary space with a small \(\Delta x\) in the complex plane. The derivative is miraculously equal to the imaginary part of the result in the limit of \(\Delta x \rightarrow 0\)!

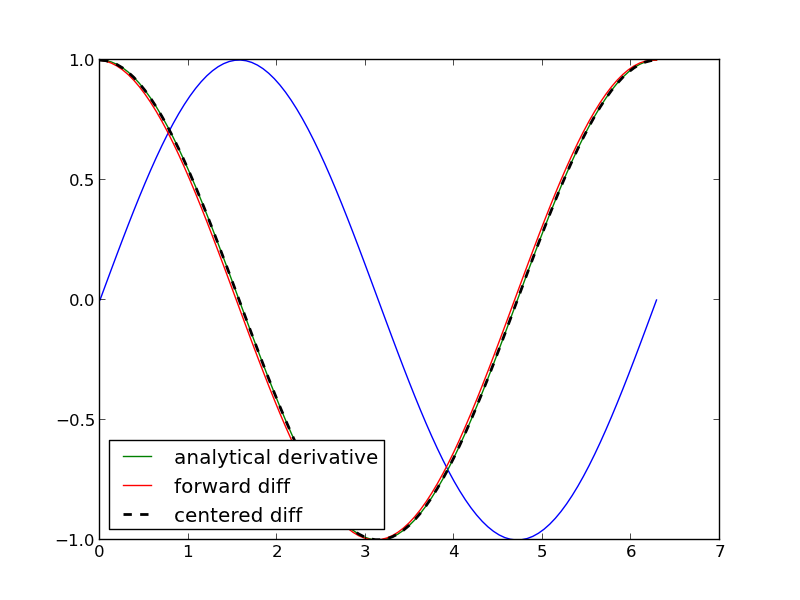

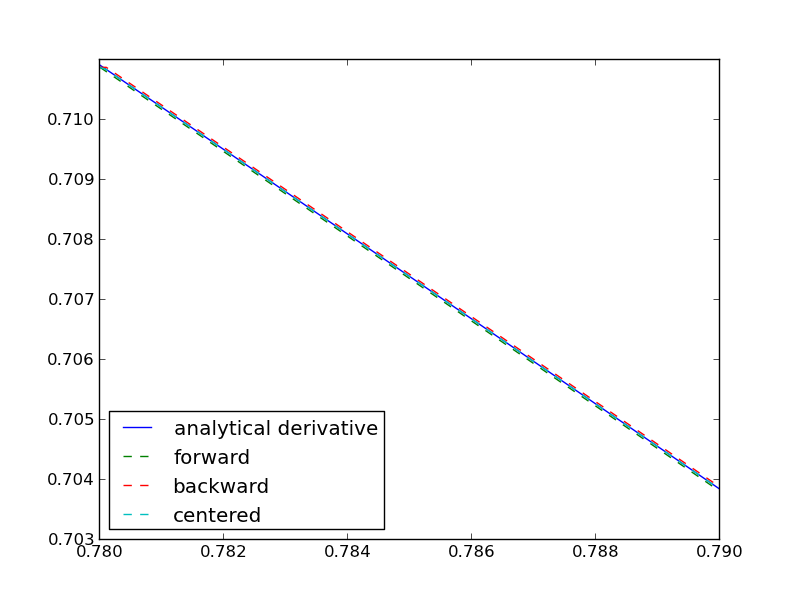

This example comes from the first link. The derivative must be evaluated using the chain rule. We compare a forward difference, central difference and complex-step derivative approximations.

import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt def f(x): return np.sin(3*x)*np.log(x) x = 0.7 h = 1e-7 # analytical derivative dfdx_a = 3 * np.cos( 3*x)*np.log(x) + np.sin(3*x) / x # finite difference dfdx_fd = (f(x + h) - f(x))/h # central difference dfdx_cd = (f(x+h)-f(x-h))/(2*h) # complex method dfdx_I = np.imag(f(x + np.complex(0, h))/h) print dfdx_a print dfdx_fd print dfdx_cd print dfdx_cd

1.77335410624 1.7733539398 1.77335410523 1.77335410523

These are all the same to 4 decimal places. The simple finite difference is the least accurate, and the central differences is practically the same as the complex number approach.

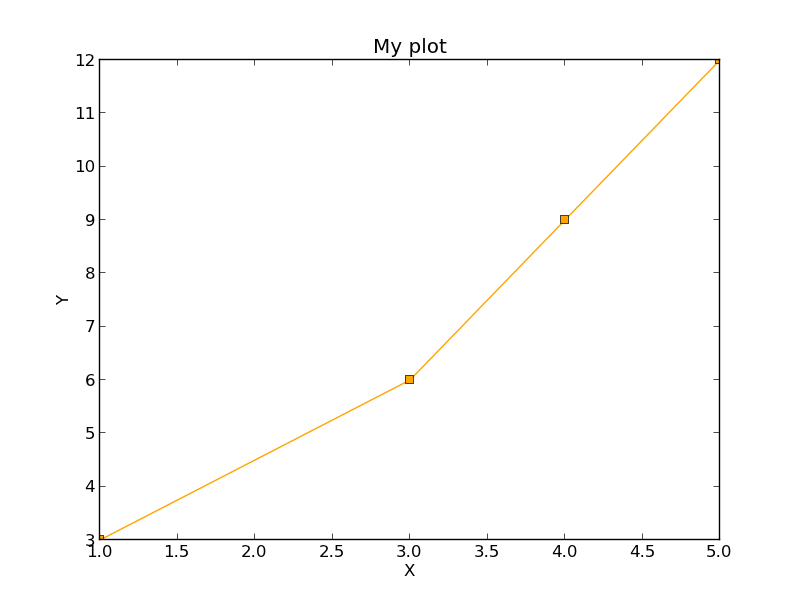

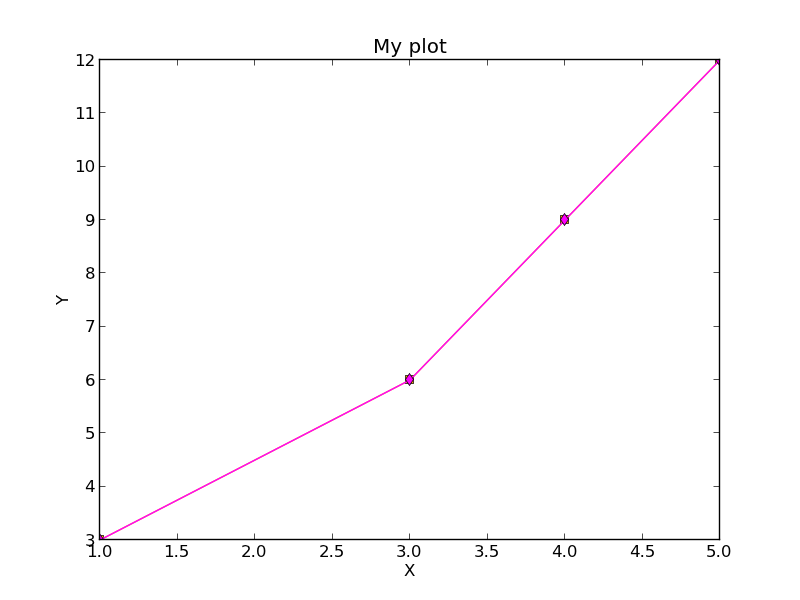

Let us use this method to verify the fundamental Theorem of Calculus, i.e. to evaluate the derivative of an integral function. Let \(f(x) = \int\limits_1^{x^2} tan(t^3)dt\), and we now want to compute df/dx. Of course, this can be done analytically, but it is not trivial!

import numpy as np from scipy.integrate import quad def f_(z): def integrand(t): return np.tan(t**3) return quad(integrand, 0, z**2) f = np.vectorize(f_) x = np.linspace(0, 1) h = 1e-7 dfdx = np.imag(f(x + complex(0, h)))/h dfdx_analytical = 2 * x * np.tan(x**6) import matplotlib.pyplot as plt plt.plot(x, dfdx, x, dfdx_analytical, 'r--') plt.show()

>>> >>> ... ... ... ... >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> c:\Python27\lib\site-packages\scipy\integrate\quadpack.py:312: ComplexWarning: Casting complex values to real discards the imaginary part

return _quadpack._qagse(func,a,b,args,full_output,epsabs,epsrel,limit)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "c:\Python27\lib\site-packages\numpy\lib\function_base.py", line 1885, in __call__

for x, c in zip(self.ufunc(*newargs), self.otypes)])

File "<stdin>", line 4, in f_

File "c:\Python27\lib\site-packages\scipy\integrate\quadpack.py", line 247, in quad

retval = _quad(func,a,b,args,full_output,epsabs,epsrel,limit,points)

File "c:\Python27\lib\site-packages\scipy\integrate\quadpack.py", line 312, in _quad

return _quadpack._qagse(func,a,b,args,full_output,epsabs,epsrel,limit)

TypeError: can't convert complex to float

>>> >>> >>> >>> Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'dfdx' is not defined

Interesting this fails.

Copyright (C) 2013 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.