Uncertainty in polynomial roots

Posted July 05, 2013 at 09:10 AM | categories: data analysis, uncertainty | tags:

Updated July 07, 2013 at 08:40 AM

Polynomials are convenient for fitting to data. Frequently we need to derive some properties of the data from the fit, e.g. the minimum value, or the slope, etc… Since we are fitting data, there is uncertainty in the polynomial parameters, and corresponding uncertainty in any properties derived from those parameters.

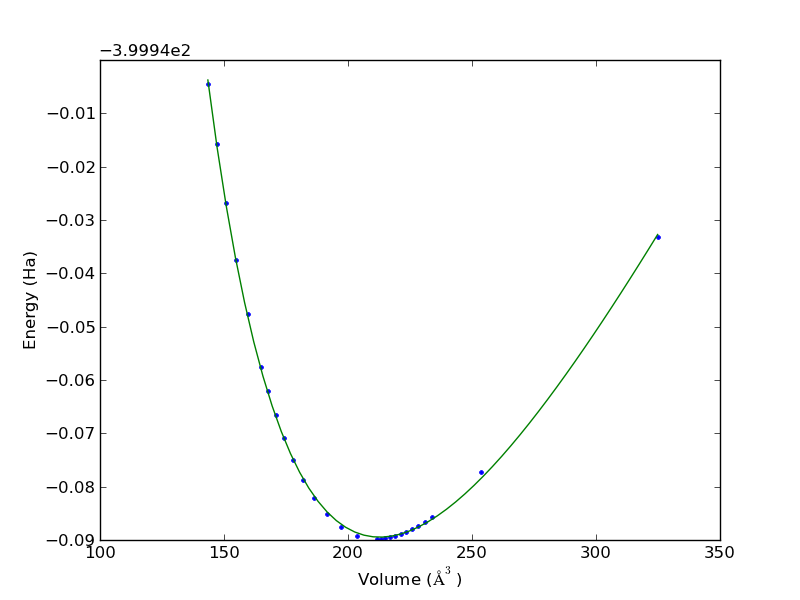

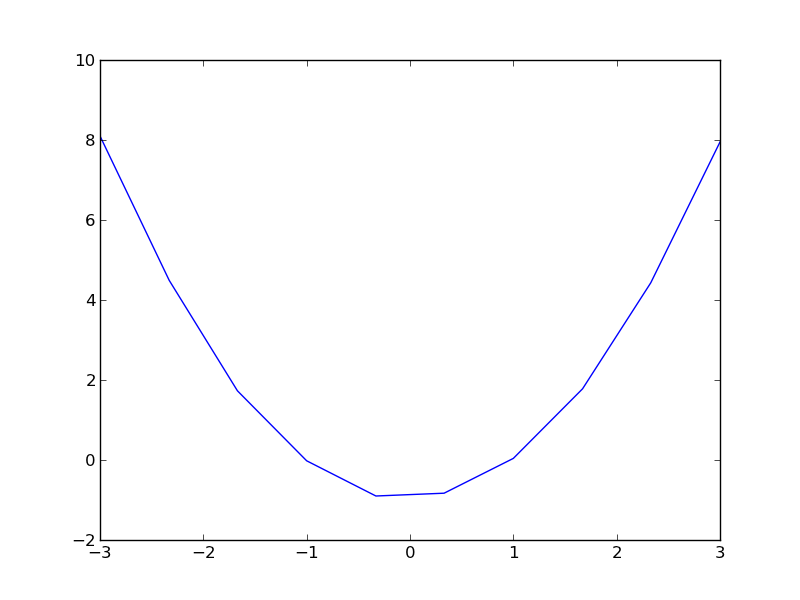

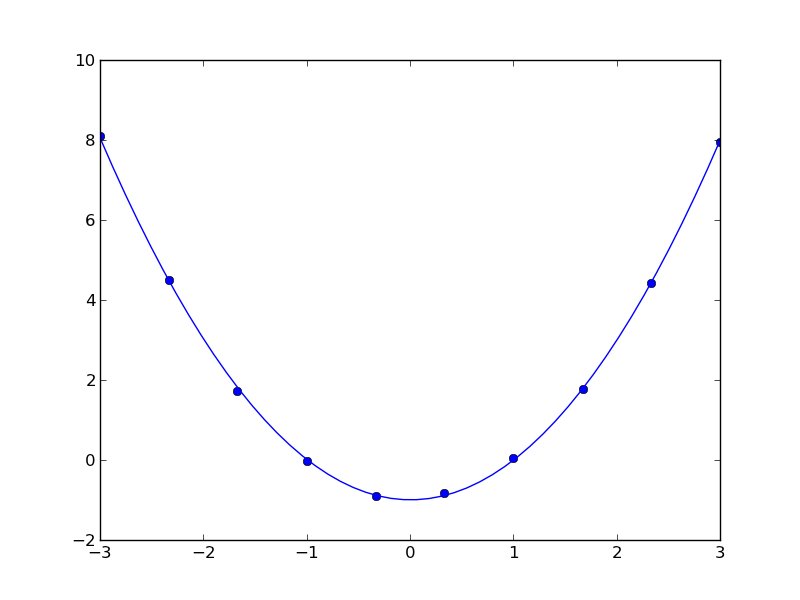

Here is our data.

| -3.00 | 8.10 |

| -2.33 | 4.49 |

| -1.67 | 1.73 |

| -1.00 | -0.02 |

| -0.33 | -0.90 |

| 0.33 | -0.83 |

| 1.00 | 0.04 |

| 1.67 | 1.78 |

| 2.33 | 4.43 |

| 3.00 | 7.95 |

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt x = [a[0] for a in data] y = [a[1] for a in data] plt.plot(x, y) plt.savefig('images/uncertain-roots.png')

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import numpy as np from pycse import regress x = np.array([a[0] for a in data]) y = [a[1] for a in data] A = np.column_stack([x**0, x**1, x**2]) p, pint, se = regress(A, y, alpha=0.05) print p print pint print se plt.plot(x, y, 'bo ') xfit = np.linspace(x.min(), x.max()) plt.plot(xfit, np.dot(np.column_stack([xfit**0, xfit**1, xfit**2]), p), 'b-') plt.savefig('images/uncertain-roots-1.png')

[-0.99526746 -0.011546 1.00188999] [[-1.05418017 -0.93635474] [-0.03188236 0.00879037] [ 0.98982737 1.01395261]] [ 0.0249142 0.00860025 0.00510128]

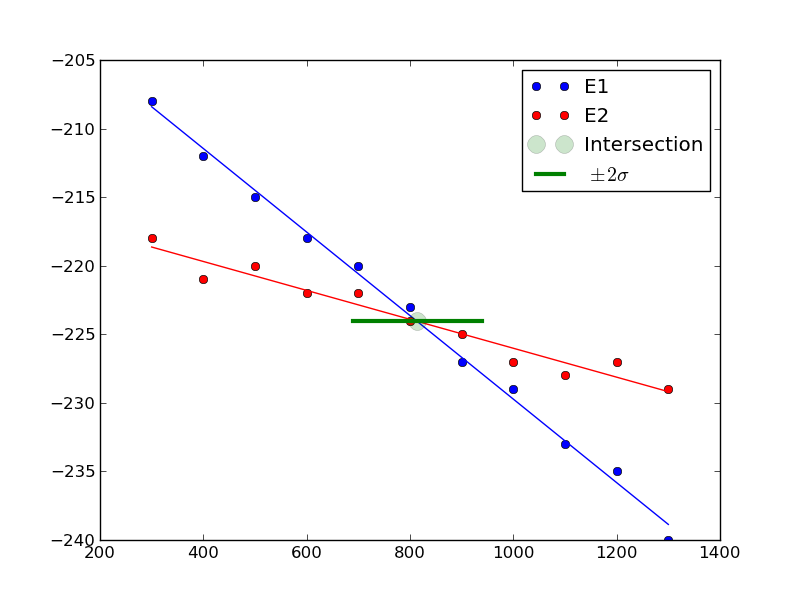

Since this is a quadratic equation, we know the roots analytically: \(x = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4 a c}{2 a}\). So, we can use the uncertainties package to directly compute the uncertainties in the roots.

import numpy as np import uncertainties as u c, b, a = [-0.99526746, -0.011546, 1.00188999] sc, sb, sa = [ 0.0249142, 0.00860025, 0.00510128] A = u.ufloat((a, sa)) B = u.ufloat((b, sb)) C = u.ufloat((c, sc)) # np.sqrt does not work with uncertainity r1 = (-B + (B**2 - 4 * A * C)**0.5) / (2 * A) r2 = (-B - (B**2 - 4 * A * C)**0.5) / (2 * A) print r1 print r2

1.00246826738+/-0.0134477390832 -0.990944048037+/-0.0134208013339

The minimum is also straightforward to analyze here. The derivative of the polynomial is \(2 a x + b\) and it is equal to zero at \(x = -b / (2 a)\).

import numpy as np import uncertainties as u c, b, a = [-0.99526746, -0.011546, 1.00188999] sc, sb, sa = [ 0.0249142, 0.00860025, 0.00510128] A = u.ufloat((a, sa)) B = u.ufloat((b, sb)) zero = -B / (2 * A) print 'The minimum is at {0}.'.format(zero)

The minimum is at 0.00576210967034+/-0.00429211341136.

You can see there is uncertainty in both the roots of the original polynomial, as well as the minimum of the data. The approach here worked well because the polynomials were low order (quadratic or linear) where we know the formulas for the roots. Consequently, we can take advantage of the uncertainties module with little effort to propagate the errors. For higher order polynomials, we would probably have to do some wrapping of functions to propagate uncertainties.

Copyright (C) 2013 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.