Building atomic clusters in ase

Posted December 22, 2014 at 08:55 AM | categories: ase, python | tags:

I was perusing the ase codebase, and came across the cluster module . This does not seem to be documented in the main docs, so here are some examples of using it. The module provides some functions to make atomic clusters for simulations.

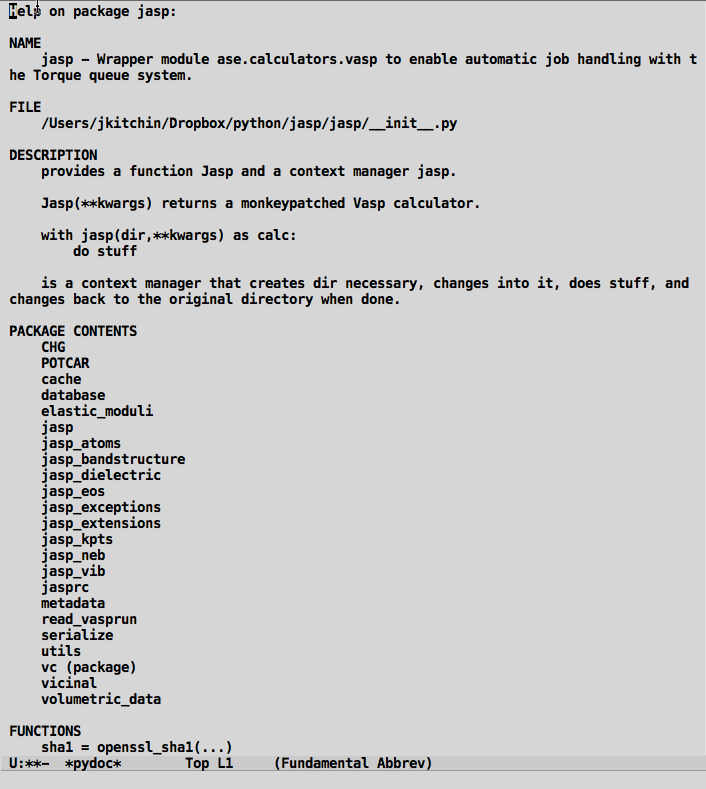

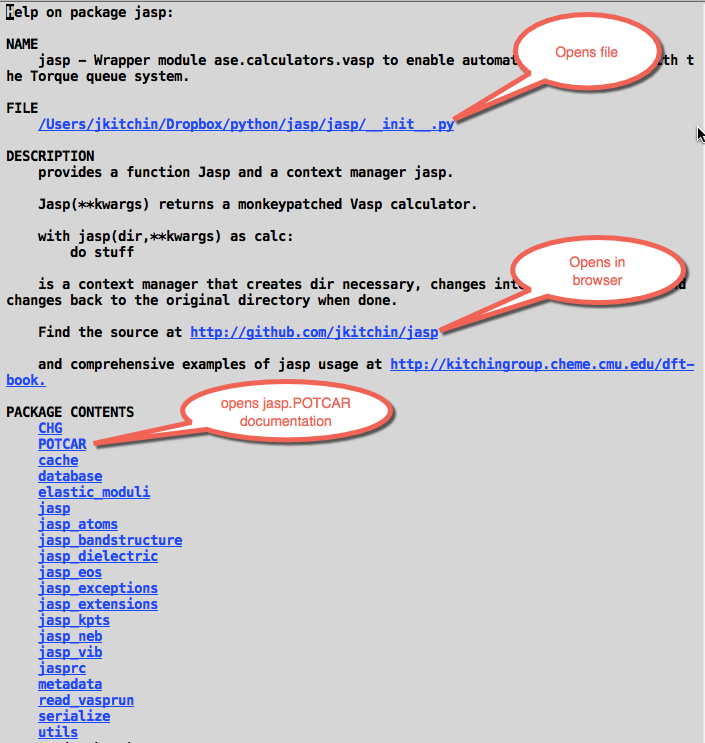

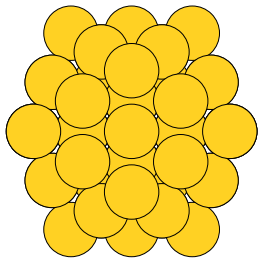

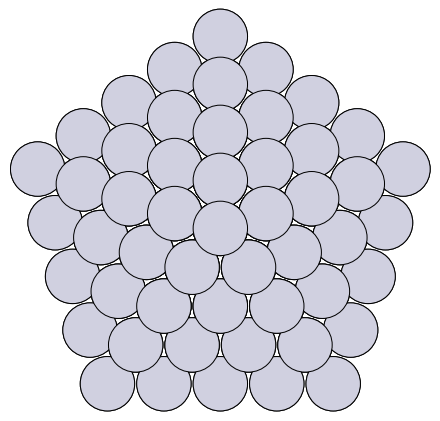

Below I show some typical usage. First, we look at an icosahedron with three shells.

from ase.cluster.icosahedron import Icosahedron from ase.io import write atoms = Icosahedron('Au', noshells=3) print atoms write('images/Au-icosahedron-3.png', atoms)

Atoms(symbols='Au55', positions=..., tags=..., cell=[9.816495585723144, 9.816495585723144, 9.816495585723144], pbc=[False, False, False])

Even with only three shells, there are already 55 atoms in this cluster!

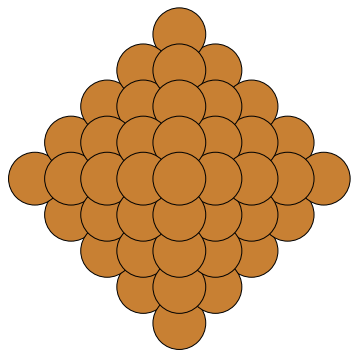

How about a decahedron? There are more parameters to set here. I am not sure what the depth of the Marks re-entrance is.

from ase.cluster.decahedron import Decahedron from ase.io import write atoms = Decahedron('Pt', p=5, # natoms on 100 face normal to 5-fold axis q=2, # natoms 0n 100 parallel to 5-fold axis r=0) # depth of the Marks re-entrance? print('#atoms = {}'.format(len(atoms))) write('images/decahedron.png', atoms)

#atoms = 156

You can see the 5-fold symmetry here. We can make octahedra too. Here, the length is the number of atoms on the edge.

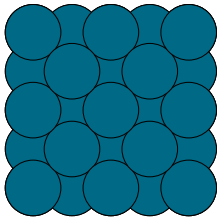

from ase.cluster.octahedron import Octahedron from ase.io import write atoms = Octahedron('Cu', length=5) print atoms write('images/octahedron.png', atoms)

Cluster(symbols='Cu85', positions=..., cell=[14.44, 14.44, 14.44], pbc=[False, False, False])

Finally, we can make particles based on a Wulff construction! We provide a list of surfaces, and their surface energies, with an approximate size we want, the structure to make the particle in, and what to do if there is not an exact number of atoms matching our size. We choose to round below here, so that the particle is not bigger than our size. In this example I totally made up the surface energies, with (100) as the lowest, so the particle comes out looking like a cube.

from ase.cluster.wulff import wulff_construction from ase.io import write atoms = wulff_construction('Pd', surfaces=[(1, 0, 0), (1, 1, 1), (1, 1, 0)], energies=[0.1, 0.5, 0.15], size=100, structure='fcc', rounding='below') print atoms write('images/wulff.png', atoms)

Cluster(symbols='Pd63', positions=..., cell=[7.779999999999999, 7.779999999999999, 7.779999999999999], pbc=[False, False, False])

This is one handy module, if you need to make clusters for some kind of simulation!

Copyright (C) 2014 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.

Org-mode version = 8.2.10