New publication - Spin-informed universal graph neural networks for simulating magnetic ordering

Posted July 17, 2025 at 08:07 PM | categories: publication, news | tags:

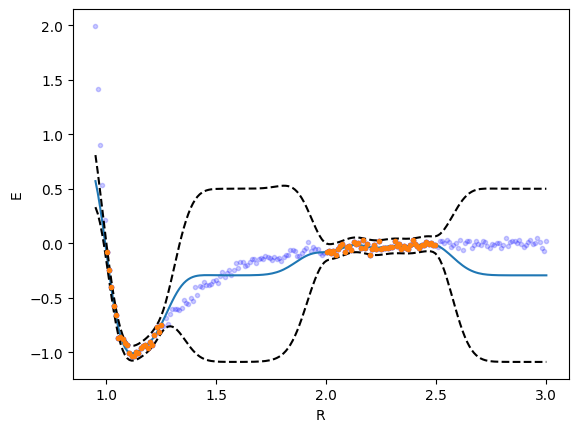

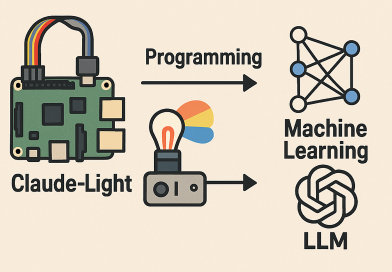

In this work, we developed a data-efficient, spin-informed graph neural network framework that augments universal machine-learning interatomic potentials with explicit spin coordinates and initial magnetic-moment guesses, while rigorously preserving the physical symmetries of collinear magnetism. This allows us to predict both the magnitude and direction of atomic spins in bulk and surface materials. By integrating a closed-loop anomaly detection pipeline based on Gaussian mixture models and z-score outlier filtering, we uncovered and corrected mislabeled DFT data, substantially improving dataset quality and model robustness. The resulting SI-GemNet-OC model achieves state-of-the-art accuracy, dramatically speeds up DFT convergence (e.g., reducing SCF cycles for GdDyAl₄ from 211 to 28), and successfully ranks magnetic orderings across hundreds of compounds with a Spearman’s ρ of 0.896. Importantly, we also show that this approach generalizes to complex surface and adsorbate-induced spin configurations, offering a powerful new tool for high-throughput discovery of magnetic materials.

@article{xu-2025-spin-infor, author = {Wenbin Xu and Rohan Yuri Sanspeur and Adeesh Kolluru and Bowen Deng and Peter Harrington and Steven Farrell and Karsten Reuter and John R. Kitchin }, title = {Spin-Informed Universal Graph Neural Networks for Simulating Magnetic Ordering}, journal = {Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences}, volume = 122, number = 27, pages = {e2422973122}, year = 2025, doi = {10.1073/pnas.2422973122}, URL = {https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.2422973122}, eprint = {https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.2422973122}, }

Copyright (C) 2025 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.

Org-mode version = 9.8-pre