Integrating the batch reactor mole balance

Posted February 18, 2013 at 09:00 AM | categories: ode | tags: reaction engineering

Updated March 03, 2013 at 10:36 AM

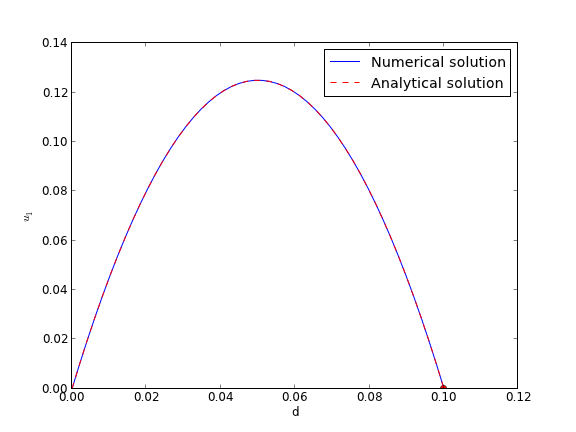

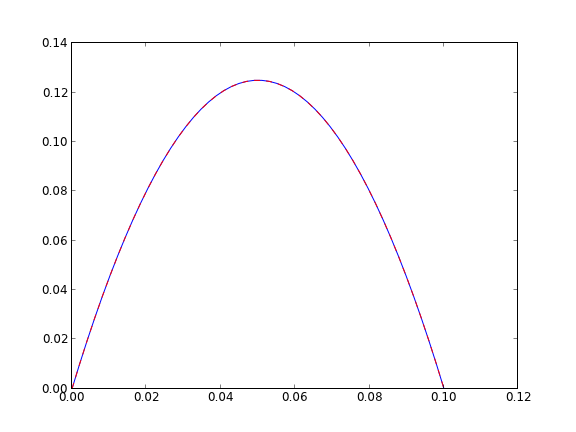

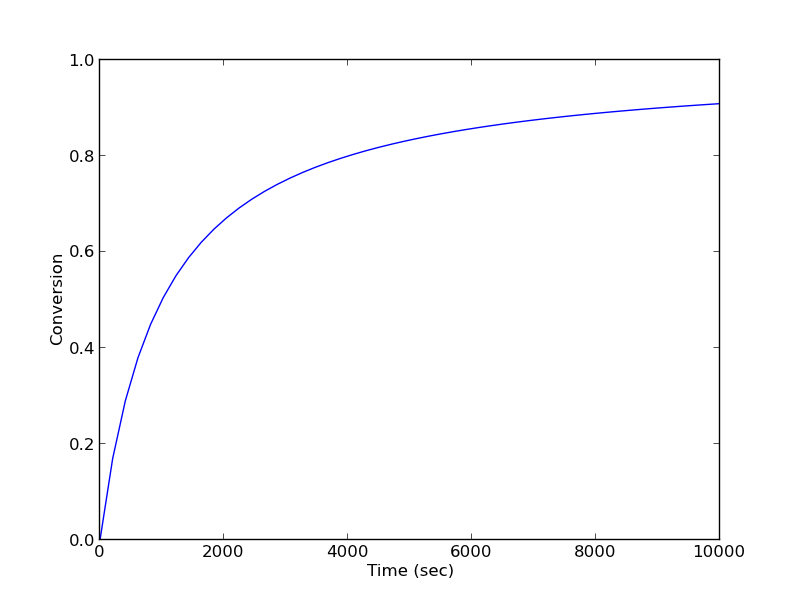

An alternative approach of evaluating an integral is to integrate a differential equation. For the batch reactor, the differential equation that describes conversion as a function of time is:

\(\frac{dX}{dt} = -r_A V/N_{A0}\).

Given a value of initial concentration, or volume and initial number of moles of A, we can integrate this ODE to find the conversion at some later time. We assume that \(X(t=0)=0\). We will integrate the ODE over a time span of 0 to 10,000 seconds.

from scipy.integrate import odeint import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt k = 1.0e-3 Ca0 = 1.0 # mol/L def func(X, t): ra = -k * (Ca0 * (1 - X))**2 return -ra / Ca0 X0 = 0 tspan = np.linspace(0,10000) sol = odeint(func, X0, tspan) plt.plot(tspan,sol) plt.xlabel('Time (sec)') plt.ylabel('Conversion') plt.savefig('images/2013-01-06-batch-conversion.png')

You can read off of this figure to find the time required to achieve a particular conversion.

Copyright (C) 2013 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.