Literate programming example with Fortran and org-mode

Posted February 04, 2014 at 10:22 AM | categories: org-mode, literate-programming | tags:

Updated February 06, 2014 at 10:28 AM

Table of Contents

Update: see a short video of how this post works here: video

I want to illustrate the literate programming capabilities of org-mode. One idea in literate programming is to have code in blocks surrounded by explanatory text. There is a process called "tangling", which extracts the code, and possibly compiles and runs it. I have typically used python and emacs-lisp in org-mode, but today we look at using Fortran.

The first simple example is a hello world fortran program. Typically you create a file containing code like this:

PROGRAM hello PRINT *, "Hello world" END PROGRAM hello

That file can be named something like hello.f90. We specify that in the source block header like this:

:tangle hello.f90

There are a variety of ways to build your program. Let us create a makefile to do it. We will specify that this block is tangled to a Makefile like this:

:tangle Makefile

Our Makefile will have three targets:

- hello, which compiles our program to an executable called a.out.

- execute, which depends on hello, and runs the executable

- clean, which deletes a.out if it exists

hello: hello.f90 gfortran hello.f90 execute: hello ./a.out clean: rm -f a.out *.o

Now, we can run

elisp:(org-babel-tangle), which will extract these files to the current directory. Here is evidence that the files exist.

ls

hello.f90 literate.org Makefile

Let us go a step further, and use the makefile to execute our program. The first time you run this, you will see that the

make clean execute

rm -f a.out *.o gfortran hello.f90 ./a.out Hello world

That works well! The only really inconvenient issue is that if you update the Fortran code above, you have to manually rerun

elisp:(org-babel-tangle), then run the

make execute command. We can combine that in a single block, where you do both things at once.

(org-babel-tangle)

(shell-command-to-string "make clean execute")

rm -f a.out *.o gfortran hello.f90 ./a.out Hello world

That is it in a nutshell. We had a source block for a Fortran program, and a source block for the Makefile. After tangling the org-file, we have those files available for us to use. Next, let us consider a little more complicated example.

1 A slightly more complicated example.

Now, let us consider a Fortran code with two files. We will define a module file, and a program file. The module file contains a function to compute the area of a circle as a function of its radius. Here is our module file, which is tangled to circle.f90.

MODULE Circle

implicit None

public :: area

contains

function area(r)

implicit none

real, intent(in) :: r

real :: area

area = 3.14159 * r**2

return

end function area

END MODULE Circle

Now, we write a program that will print a table of circle areas. Here we hard-code an array of 5 radius values, then loop through the values and get the area of the circle with that radius. We will print some output that generates an org-mode table . In this program, we use our module defined above.

program main use circle, only: area implicit none integer :: i REAL, DIMENSION(5) :: R R = (/1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 /) print *, "#+tblname: circle-area" do i = 1, 5 print *, "|", R(i), "|", area(R(i)), "|" end do end program main

Now, we make a makefile that will build this program. I use a different name for the file, since we already have a Makefile in this directory from the last example. I also put @ at the front of each command in the makefile to suppress it from being echoed when we run it. Later, we will use the makefile to compile the program, and then run it, and we only want the output of the program.

The compiling instructions are more complex. We have to compile the circle module first, and then the main program. Here is our makefile.

circle: @gfortran -c circle.f90 main: circle @gfortran -c main.f90 @gfortran circle.o main.o -o main clean: @rm -f *.o main

Now, we run this block, which tangles out our new files.

(org-babel-tangle)

| main.f90 | circle.f90 | hello.f90 | makefile-main | Makefile |

Note that results above show we have tangled all the source blocks in this file. You can limit the scope of tangling, by narrowing to a subtree, but that is beyond our aim for today.

Finally, we are ready to build our program. We specify the new makefile with the -f option to make. We use the clean target to get rid of old results, and then the main target with builds the program. Since main depends on circle, the circle file is compiled first.

Note in this block I use this header:

#+BEGIN_SRC sh :results raw

That will tell the block to output the results directly in the buffer. I have the fortran code prename the table, and put | around the entries, so this entry is output directly as an org table.

make -f makefile-main clean main ./main

| 1.000000 | 3.141590 |

| 2.000000 | 12.56636 |

| 3.000000 | 28.27431 |

| 4.000000 | 50.26544 |

| 5.000000 | 78.53975 |

It takes some skill getting used to using :results raw. The results are not replaced if you run the code again. That can be inconvenient if you print a very large table, which you must manually delete.

Now that we have a named org table, I can use that table as data in other source blocks, e.g. here in python. You define variables in the header name by referring to the tblname like this.

#+BEGIN_SRC python :var data=circle-area

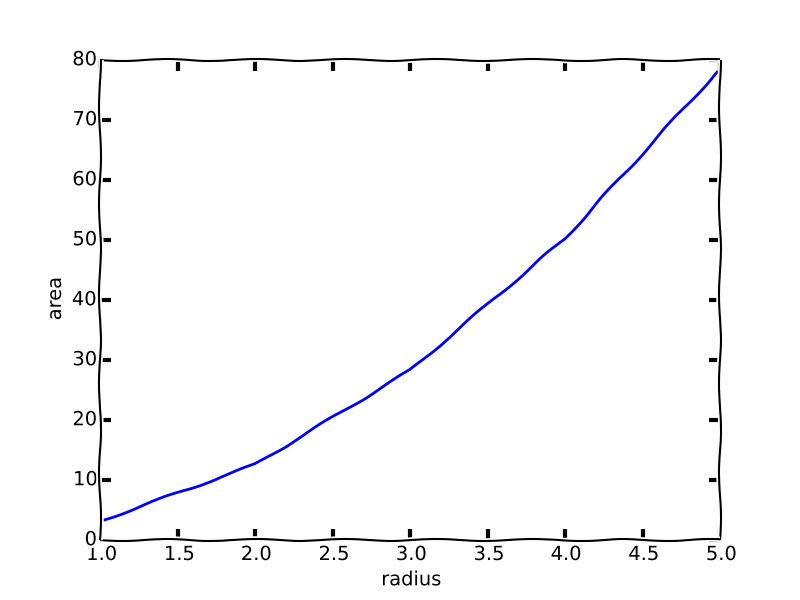

Then, data is available as a variable in your code. Let us try it and plot the area vs. radius here. For more fun, we will make the plot xkcd , so it looks like I sketched it by hand.

import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt plt.xkcd() print data # data is a list data = np.array(data) plt.plot(data[:, 0], data[:, 1]) plt.xlabel('radius') plt.ylabel('area') plt.savefig('circle-area.png')

[[1.0, 3.14159], [2.0, 12.56636], [3.0, 28.27431], [4.0, 50.26544], [5.0, 78.53975]]

It appears the area increases quadratically with radius. No surprise there! For fun, let us show that. If we divide each area by \(r^2\), we should get back π. Let us do this in emacs-lisp, just to illustrate how flexibly we can switch between languages. In lisp, the data structure will be a list of items like ((radius1 area1) (radius2 area2)…). So, we just map a function that divides the area (the second element of an entry) by the square of the first element. My lisp-fu is only average, so I use the nth function to get those elements. We also load the calc library to get the math-pow function.

(require 'calc) (mapcar (lambda (x) (/ (nth 1 x) (math-pow (nth 0 x) 2))) data)

| 3.14159 | 3.14159 | 3.14159 | 3.14159 | 3.14159 |

Indeed, we get π for each element, which shows in fact that the area does increase quadratically with radius.

You can learn more about tangling source code from org-mode here http://orgmode.org/manual/Extracting-source-code.html .

2 Summary key points

- You can organize source files in org-mode as source blocks which can be "tangled" to "real" source code.

- You can build into your org-file(s) even the Makefile, or other building instructions.

- You can even run the build program, and the resulting programs from org-mode to capture data.

- Once that data is in org-mode, you can reuse it in other source blocks, including other languages.

What benefits could there be for this? One is you work in org-mode, which allows you to structure a document in different ways than code does. You can use headings to make the hierarchy you want. You can put links in places that allow you to easily navigate the document. Second, you can build in the whole workflow into your document, from building to execution. Third, you could have a self-contained file that extracts what someone else needs, but which has documentation and explanation built into it, which you wrote as you developed the program, rather than as an afterthought. You can still edit each block in its native emacs-mode, and have org-mode too. That is something like having cake, and eating it too!

Downsides? Probably. Most IDE/project type environments are designed for code. These tools offer nice navigation between functions and files. I don't use those tools, but I imagine if you are hooked on them, you might have to learn something new this way.

Copyright (C) 2014 by John Kitchin. See the License for information about copying.

Org-mode version = 8.2.5h